A Stupid Boy

Part 7: The Buckfoot Gang

Continuing the progress of the Robert P. Boatright trial for the murder of Charles Woodson.

The defense witnesses kept on coming. Defense lawyer F.D. Turner called Francis Whittaker to the stand to relate his experience of Robert P. Boatright, and he echoed the assessment that the boy was sprightly, of good habits, bright, and intelligent before his illness but seemed dull afterward.

Prosecutor James Normile cross-examined Whittaker and asked how he became acquainted with the defendant. Mr. Whittaker explained he was a carpenter and had worked for the boy’s father when he started his carpentry business in 1866. He said when he saw the defendant again in 1870, the boy appeared not to understand anything said to him. Asked to elaborate, he said Robert sometimes helped around the shop but once had handed Whittaker a saw when he’d asked for a hatchet. He remarked that his father had not had the boy treated for insanity, as though was the obvious course.

Attorney Turner objected based on relevance and Attorney Normile replied a somewhat cagy, “The court will find out…before we get through.” Normile may have been required to give a more informative answer, but if so, it wasn’t mentioned.

Next up was Thomas J. Henley, local publisher of the Fireside Visitor (also referred to as Fireside Weekly and Plain Reasoner). This was a serialized religious tract written by David C. Candland (birth name) Kimball (adoptive name) to further the religious tenets of the Mormon Church.

Mr. Henley testified that he first met Robert at his brother’s funeral in November of 1874. He said “The boy didn’t seem to know his brother was dead; he appeared a stupid-looking boy.” The word ‘stupid’ has, in the past, been used to describe a state of confusion or disorientation, as in stupefied. To our ears, it sounds quite harsh.

That brusque statement wasn’t the end of it from Mr. Henley. On cross, he said this: “I have seen 102 idiots in my time. I have seen a great many idiots have the same style of forehead and face as the prisoner.”

I have to wonder if Thomas J. Henley was a proponent of Phrenology. As a witness, he can’t compare Robert’s behavior pre-illness to post-illness because he didn’t meet him until afterward. He also is not testifying toward the idea that the illness caused insanity, but expresses his opinion that the defendant’s skull structure is an indication of idiocy.

I’m curious about someone who keeps count of the people he has met whom he deems to be idiots. Did he carry large-scale calipers on his person to measure people’s forehead width or was he eyeballing it?

Henley continued, “At the funeral, he [Robert] seemed to be unconscious. I don’t think it was caused by grief; he did not seem to be borne down by grief. He seemed to be thinking about something else, did not pay any attention to what was going on. I have heard his conduct discussed before. He did not appear to have any feeling at all.” An observation which might also be applied to Mr. Henley. Tact was not a doctrine Mr. Henley subscribed to.

That being said, it is possible Mr. Henley was referring to people who suffered from epilepsy, and those sufferers were referred to as “idiots” in those days. Even so, no explanation of why Mr. Henley claimed such a significant history of meeting people with epilepsy. Wondering if he might have had some medical experience, I did a bit of research on Mr. Henley. At the time of this trial, besides being a publisher, he was the Secretary for a political action group called the Scheme and Charter. At the time, the group was involved in an upcoming election regarding keeping the City of St. Louis an independent city without inclusion in a county, as it remains today.

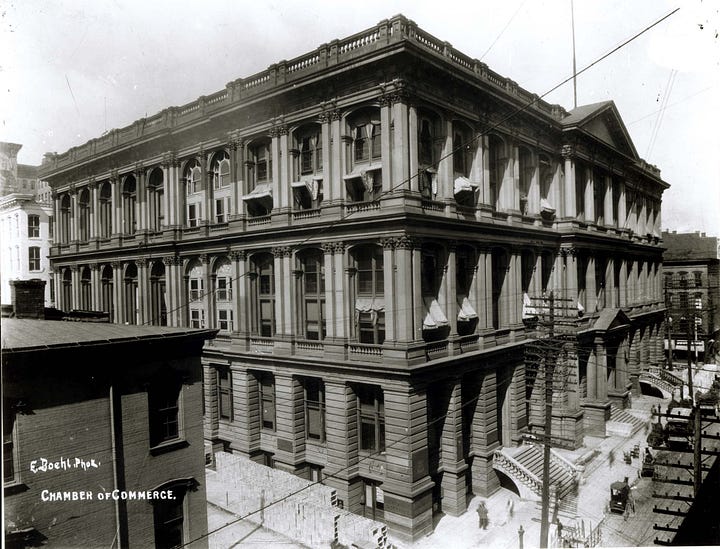

The group’s offices were located within the Merchant’s Exchange which stood across the street from the courthouse. It no longer exists. Two years later, in 1878, Henley was running for the office of Commissioner of Supplies for St. Louis. Since the mid-1860’s when he first appeared in the City Directory, he was listed as being in real estate, a collector, and eventually a publisher. Thomas Henley was a member of Polar Star Lodge #79 of the Masons. He died July 13, 1887 at 55.

Stonecutter Alex S. Hughes was Robert’s supervisor in 1875, the year after Oscar was killed. He said Robert’s work was inconsistent; sometimes it was good, sometimes he’d chip a piece off from a finished work, and sometimes he didn’t know what to do. Mr. Hughes said the day before Charles Woodson’s trial began, he’d asked Robert to do some stone work for him but he’d refused, saying, “I can’t get that ****** out of my head,” using a racial epithet for Charles. Mr. Hughes said Robert sometimes complained of pain on the left side of his head and was “more stupid than usual” at those times.

On cross-examination, his testimony is contradictory in a way. Hughes said Robert had worked for him between five and seven months. He explained that he did the cornices and decorative work himself and Robert worked on plain stone and window sills. He testified that he had seen Robert knock a piece off a stone once. He then said Robert had done some very good work the day before he murdered Charles Woodson, which contradicts his statement that Robert had refused to work that day.

On that note, the court broke for lunch and resumed at 2:15 p.m. by calling William Sinclair, also a stonecutter who appears to have owned the business where both Alex and Robert worked. He said the defendant had been in his employ for six or seven months. He felt Robert was a dull boy and, at times, would not reply when asked a question. He testified that he’d twice seen Robert destroy a finished stone with an axe.

Mr. Sinclair described Robert as being unlike any other boy he knew. He seemed very willing to work, but had moody, gloomy times. Robert appeared eager to learn everything about stone work for houses but didn’t advance like the other boys he hired. He admitted he had let him go twice, but both times took him back when his father had petitioned him to do so. He said he wasn’t a particular friend of Robert M.’s, but took his son back to work because at times he did “very good work.” He said it had never occurred to him that Robert was insane, just that he was a strange boy who seemed very angry at times.

The defense asked him on re-direct if he would say if he felt Robert was sane or insane but Mr. Sinclair declined to commit to that either way.

Charles Ream was a cabinetmaker/upholsterer who had known Robert since May of 1872 when he employed him for six weeks. He hired him at his father’s request and kept him on until June when he could no longer “do anything with him.” He was “gloomy and sad,” and would sometimes work a couple of hours and then just stop.

Mr. Ream said on the morning of the Woodson trial, when the murder occurred, Robert came into the shop and said he would be going to the courthouse that day. Mr. Ream asked Robert what was going on. He replied that his father had done something wrong, that he had “whipped the colored boy,” and he thought the court should deal with him.

During cross and redirect, Mr. Ream said he judged the boy to be of bad temper, moody, and willful, but didn’t judge him to be insane. Because of that, he also judged it was best to let him go. He didn’t think Robert’s version of his father being in court to be particularly strange; he just thought he was telling the truth.

A. J. Buck, a clerk, testified that he was in the offices of Dr. Nidelet on the morning of the murder. James C. Nidelet, MD was the Boatright family’s physician. Mr. Buck said a boy, whom he identified as Robert, rushed into the office. He appeared out of breath, very excited, and had a piece of paper in his hand. Mr. Buck saw the boy stride right into the inner office without knocking and quickly come back out.

Dr. Nidelet was in his office that morning and responded to the note Robert gave him by going to the court where the Woodson trial was being held in order to give his statement, as was requested.

At this point, defense attorney Turner requested the case be laid over since Dr. Nidelet was unable to appear at that time due to his associate being out sick. Judge Lindley declined to delay proceedings and suggested the defense move on to another witness and calling the doctor at a later time.

Reluctantly, the defense did as the judge asked. The next witness was the much anticipated father of the defendant, Robert M. Boatright.

Enjoyed this Cynthia. I have a Phrenology head sitting in my office. Picked it up at a flea market many years ago. Didn’t know anything about Phrenology. Did some reading and discovered this was a widely accepted approach to understanding human behavior. Surprising and interesting.

It’s incredible how much testimony you’ve been able to recreate and share in this story, and in these last two episodes especially. Fabulous work in weaving it all together into a coherent narrative while pointing out the contradictions and historical baggage.

And seriously, who keeps track of how many idiots they’ve met!? 🤦🏼♀️