This is the ninth post in my series of biographical vignettes of the ladies who signed an 1882 Autograph book I found at a flea market. The young women were classmates at St. Mary’s Academy, a boarding school for girls on the campus of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana.

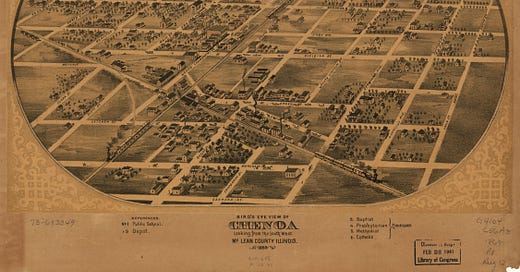

Anastasia Agnes Dillon was born in Illinois in 1864. Her family lived in Joliet in 1850 and 1860, but moved a bit south to Chenoa between 1860-70. If Agnes wasn’t born in Chenoa, she lived there soon after.

When Agnes was a child, Chenoa was still young, having been laid out in 1855-56 by Matthew T. Scott who was the son of a Kentucky banker and came to Illinois to make his fortune as a land developer. He selected the site for Chenoa by anticipating where the existing east-west Toledo-Peoria railroad would intersect with the coming north-south Chicago-Alton line. His guess was accurate. One of, if not the first, structures in Chenoa, Michael Scott’s house was built in 1855 and would have been one Agnes knew well. It was two blocks from the high school where she worked as an adult. The home still stands today.

Agnes’s father, Michael Dillon, was born in Ireland in 1834. In 1847, the Dillon family, noted as one of wealth in Ireland, crossed the Atlantic to America. The family members who traveled were adults Margaret (b. 1780-1790), John (1809), and Ellen (1812). John and Ellen’s children Patrick (1832), James (1833), and Michael (1834). The four youngest children, John (1848), Margaret (1850), Thomas (1852), and Mary (1854) were born in Illinois. There is a gap of fourteen years between Michael and John; there could have been children born after 1834 who perhaps passed away before the family emigrated or stayed behind with other family, but I haven’t seen evidence of that. The passenger list shows Ellen as John’s wife and later on she is listed as mother of the eldest boys. That doesn’t preclude John having had a first wife in Ireland who died after 1834 with John subsequently marrying Ellen, but again I don’t have evidence of that. Agnes’s mother, Anne Murphy, was also from Ireland, was born about 1840. She and Michael were married May 27, 1859.

Before I move on to Agnes’s personal history, I want to include information about her family. Family stories help to fill in and illustrate the path of a person throughout life. If their story is told devoid of the rich details of the people she descended from, grew up with, married, and experienced her life with, it can be superficial.

The Dillon family dynamic is curious, starting with the patriarch, John. John was Agnes’s paternal grandfather and his main occupation appears to have been farming. This often meant the subject owned the acreage and employed farm hands for the work which appears to be the case with John. He also owned a store in Joliet and was involved in civic offices. In 1862, he was the Troy Township Assessor (Joliet) and a Justice of the Peace; Agnes’s father Michael was the Town Clerk. The Dillon children were well-educated and Michael clearly could read and write.

John’s will was probated in 1867, when Agnes would have been about 3 years old. He left significant amounts of money (several thousands of dollars), farmland, the main house, the property with the store, and furnishings to his wife and all living children…except Michael, who received a mere $25.00. Nothing else. I don’t know if there had been a break between Michael and his father at some point, but the disparity in the will is quite noticeable, especially since Michael was the only child of his parents to have a spouse and children at the time. The discrepancy is blatant enough to appear to be meant as a slight.

The two eldest sons were priests. Among his many accolades, Patrick was President of Notre Dame University for two years, served in France for his Order for two years, and became the priest of St. Patrick’s in Chicago. He died at 36 on the evening of November 15, 1868 at his home from “internal inflammation.”

James also served in elevated positions at Notre Dame and was slated to take up the priesthood at St. Patrick’s upon his brother’s death, but before he could do so, he died of consumption (tuberculosis) only one month after his brother on December 17, 1868 at age 35.

The fourth Dillon son and the first to be born in America was John. He died sometime shortly after 1860 before reaching adulthood.

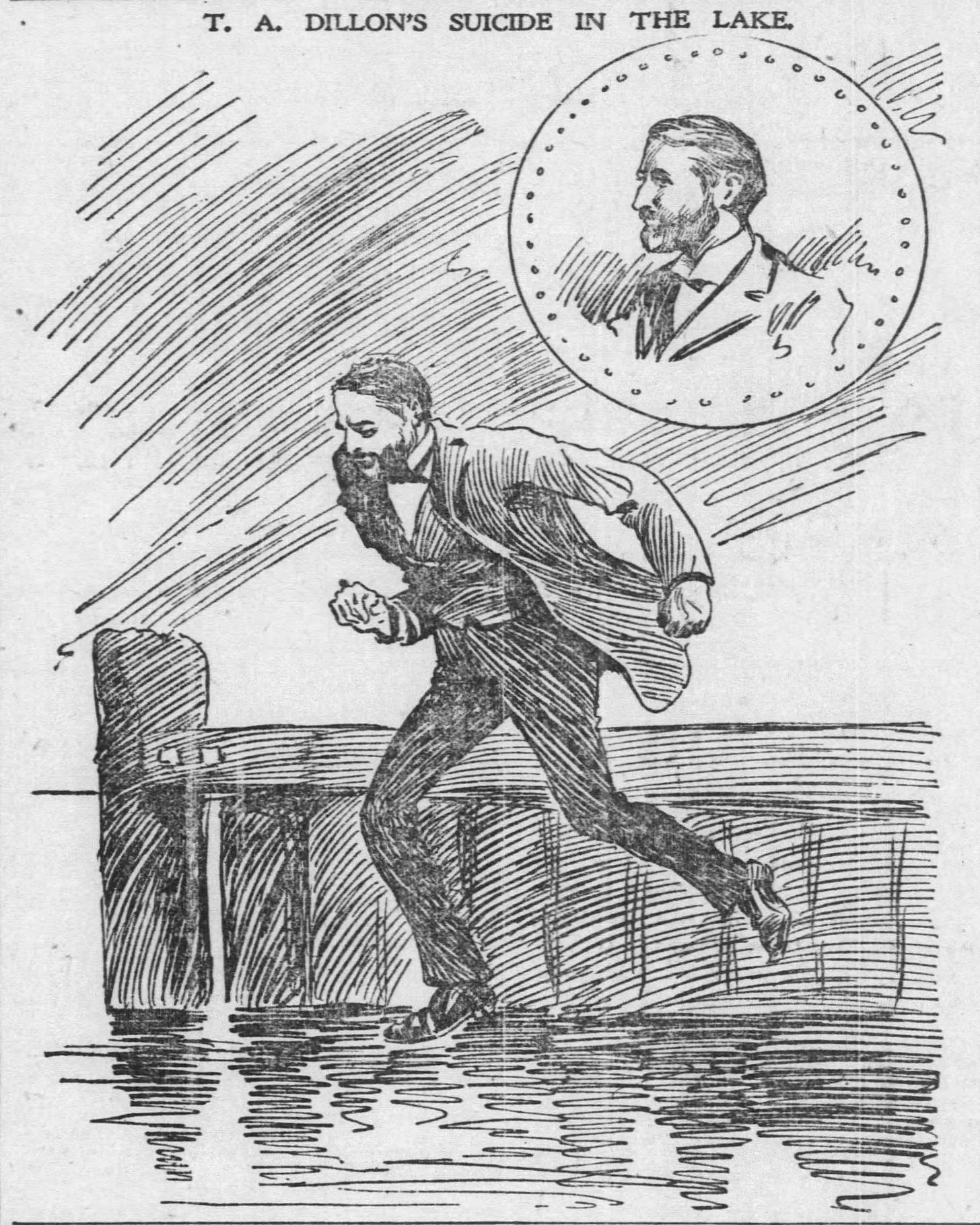

The remaining Dillon son was Thomas. His story is complicated and his suicide hints at unspoken issues. Thomas’s death on October 9, 1897 was widely reported with extensive coverage in the Chicago Chronicle and Chicago Tribune. At 45, Thomas was President of the prosperous Cavanagh Distillery which was founded by his sister Margaret’s husband, Patrick Cavanagh. Thomas was a wealthy man and his wife, Sadie née Riley, owned a large percentage of shares in the distillery. In 1880, 28-year-old Thomas was living with his sister and brother-in-law and worked as a salesman for the distillery. It seems likely that he became very close to Patrick, which might have had some relevance in his mental status.

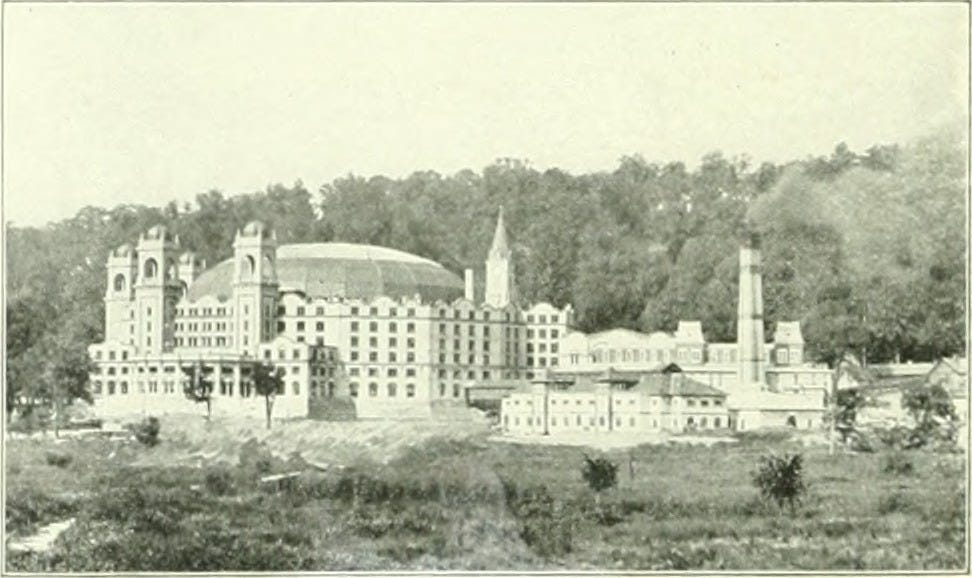

Upon being interviewed regarding Thomas’s death, colleagues and friends reported that Thomas was under “the conviction that he had an incurable illness." To me, their words could be implying he hadn’t formally been diagnosed with one. If he had, it seems more likely they’d say he had an incurable disease but no one did and no specific illness was named. Because of his symptoms, Thomas and his family had recently traveled to West Baden Springs hoping for relief, but it was unsuccessful. West Baden Springs & Hotel is still in operation in French Lick, Indiana. Below is a photo from 1897 which is how the spa would have looked when the Dillon’s visited, as well as a photo of the spa in 2011, and the interior.

On October 9, Thomas was at his office briefly where others noted his speech was incoherent. He did’t stay long, saying he had a headache and was going home, which he did, but soon left again and headed for the shore of Lake Michigan at the end of Ontario Street in Chicago. There he was seen standing at the water wall where he was observed by numerous people. Charles Closs was seated at the lakeshore and watched Thomas for over an hour because of his despairing demeanor. Mr. Closs said he decided he would go talk to him to see if he could help but when he got within a few feet, the man climbed over the wall dove into the deep water. Closs flagged down a policeman and returned to the spot, but Thomas did not resurface.

It took Officers Minden, Schaus, and White along with Charles Closs, D.J. and C.W. Fair more than half an hour to recover Thomas’s body using ropes and grappling hooks. They tried to resuscitate him but he was already gone. It seems significant that Patrick Cavanagh, the brother-in-law Thomas was close to, died on the exact same day, October 9, two years prior in 1895. His cause of death was apoplexy. Thomas’s sister, Patrick’s wife Margaret, was made Secretary of the distillery upon her husband’s death.

Three letters were found in Thomas’s pockets, but they had to be taken to the police station to be dried before they could be read. One was addressed to the distillery notifying them of his resignation, but was dated October 23 of the prior year. This was two weeks past the one-year anniversary of Patrick’s death. Had Thomas carried this letter around in his suit pocket for more than a year? The two remaining letters were no less unexpected. They were addressed to two priests at Holy Name Cathedral, Fathers Muldoon and Conway. Each contained a check in repayment of loans they had made to his wife Sadie, and further requested they loan her no more money since she had no need to borrow. Thomas left behind his wife and three children 10 years old and under. Thomas may have truly been terminally ill but he certainly seems to have been suffering from mental anguish of some sort that he had chosen not to share with anyone.

Back to Agnes’s story. When the family settled in Chenoa, Michael worked as a day laborer. During the 1860s, he served in the Civil War in the 8th Illinois Infantry. The couple had nine children of which Agnes was third. Children: Francis, Ellen, Agnes, Eugene, Mary, Katie, Thomas, Anne, Aloysius.

Michael doesn’t appear to have had quite the same prosperity as his siblings which could have at least been due in part to essentially being left out of his father’s will. I don’t know if the farm wasn’t productive enough to support the family and work was difficult to find in the rural communities, or if it was simply an opportunity to make good money for a while, but on the 1880 census, Michael was living in a boarding house in Peoria while working as a day laborer. Anne was still on the farm in Chenoa with the five youngest children per that census.

Agnes is recorded in 1880 as a student at St. Mary’s Academy in South Bend, Indiana. She was 17 years old. The cost of her tuition at St. Mary’s must have been a significant financial consideration for her parents but they clearly wanted her to have a good education. This may have played a part in Michael’s decision to work in Peoria for a time. It would turn out to be a profitable investment for Agnes, and one she seems to have fully appreciated.

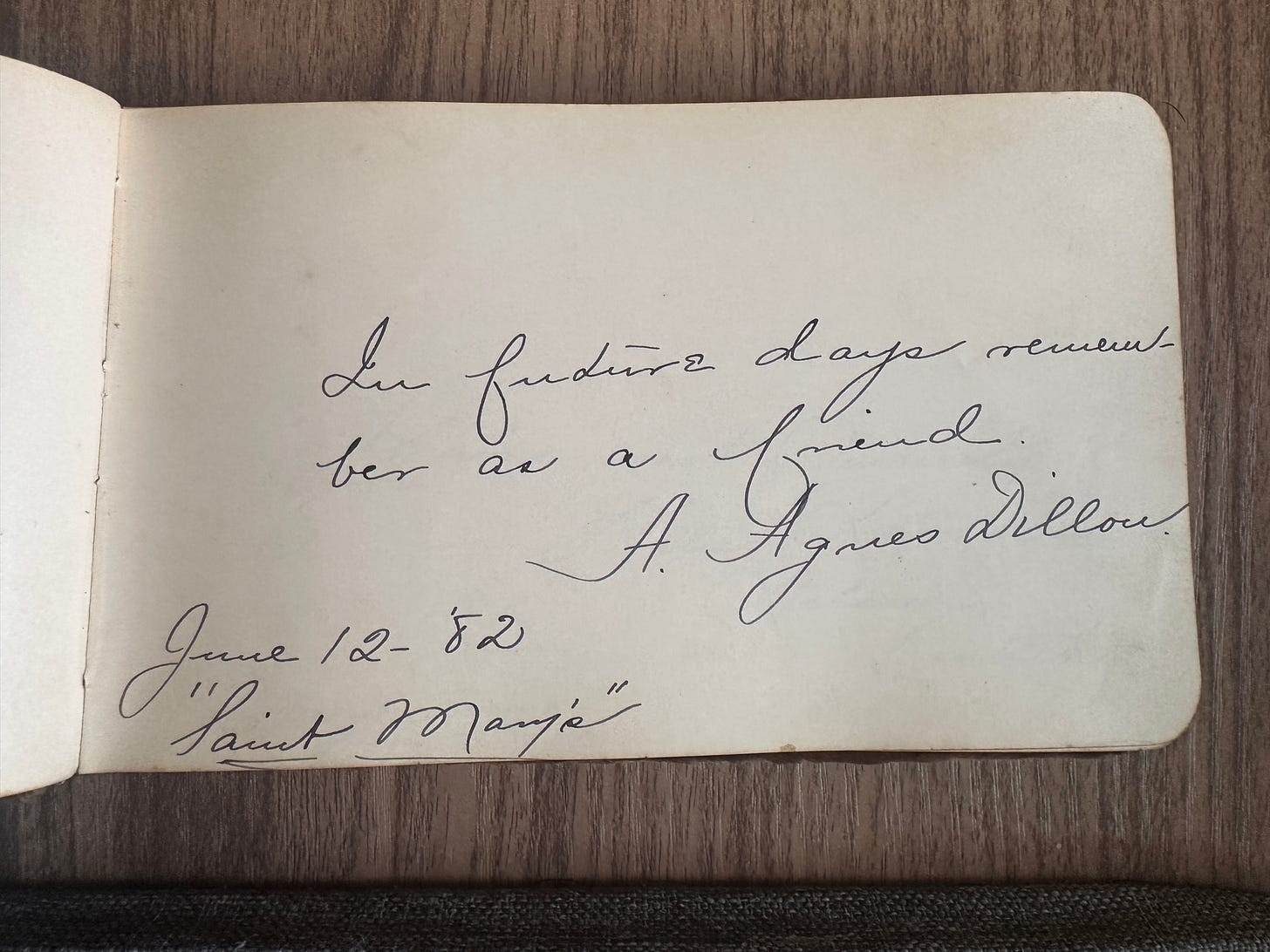

Agnes signed the autograph book in 1882, writing “In future days remember as a friend” A. Agnes Dillon. At that time, she would have been one year from graduation. Agnes’s aunt Margaret, sister to Thomas, had also attended St. Mary’s. In 1909, the Chicago Tribune noted Margaret Dillon-Cavanagh being elected President of the Alumnae Association. On June 21, 1883, the South Bend Daily Tribune detailed St. Mary’s commencement proceedings. Agnes is mentioned as reading an essay entitled The Beauty of Self Control.

In 1900, Michael was back in Chenoa with Anne but she died on August 18 the following year. Even though Michael was present and was known to be literate, it was Agnes who was appointed sole administratrix with full power of administration. Perhaps he preferred Agnes, a school administrator, to manage the paperwork.

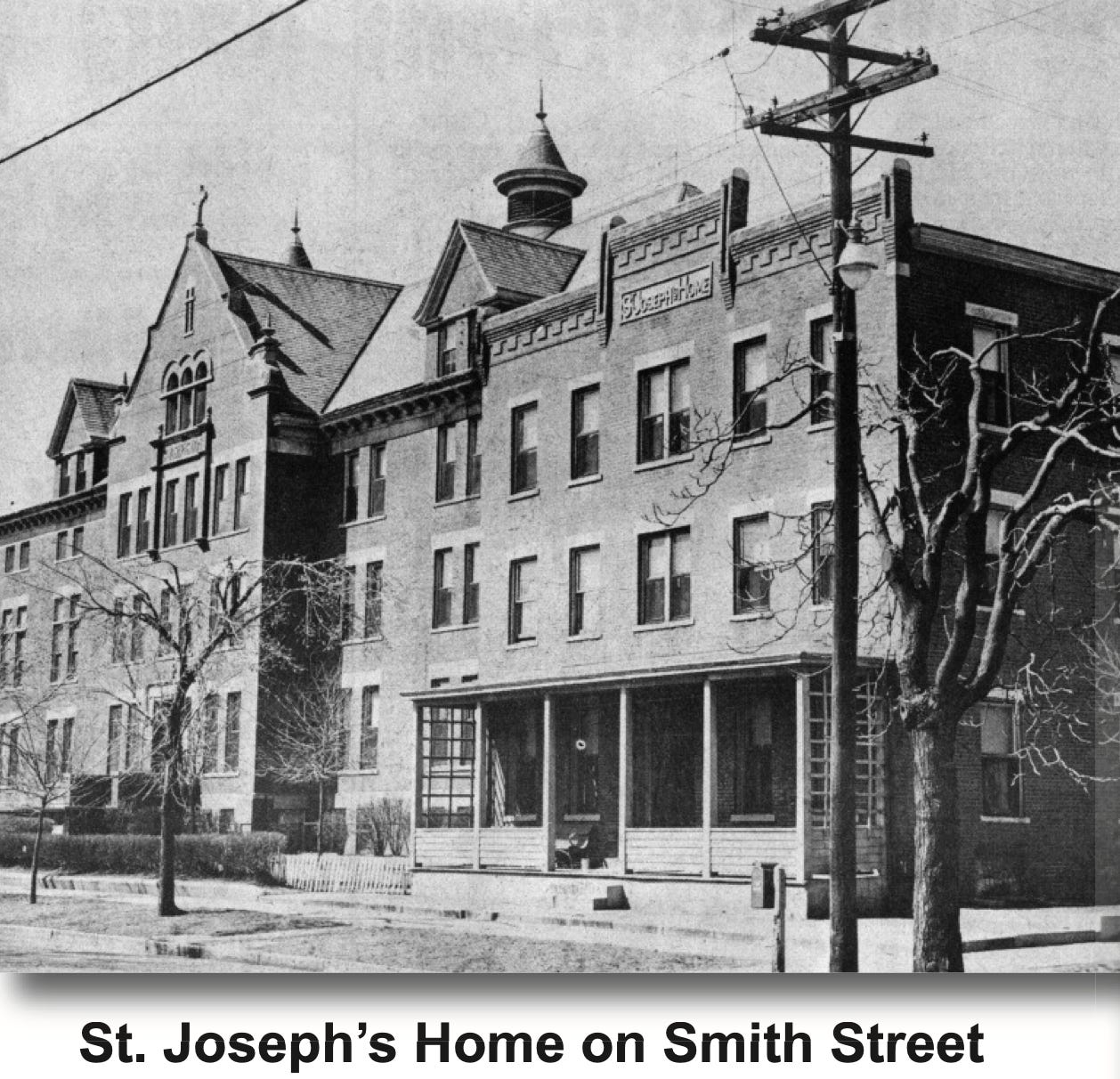

Michael was still living in the family home in Chenoa in the 1910 census which records it as free of mortgage. Because of that, I was surprised to find him living in the St. Joseph’s Home for the elderly in Peoria, at age 85, rather than with family, either in South Dakota, Illinois, or Texas.

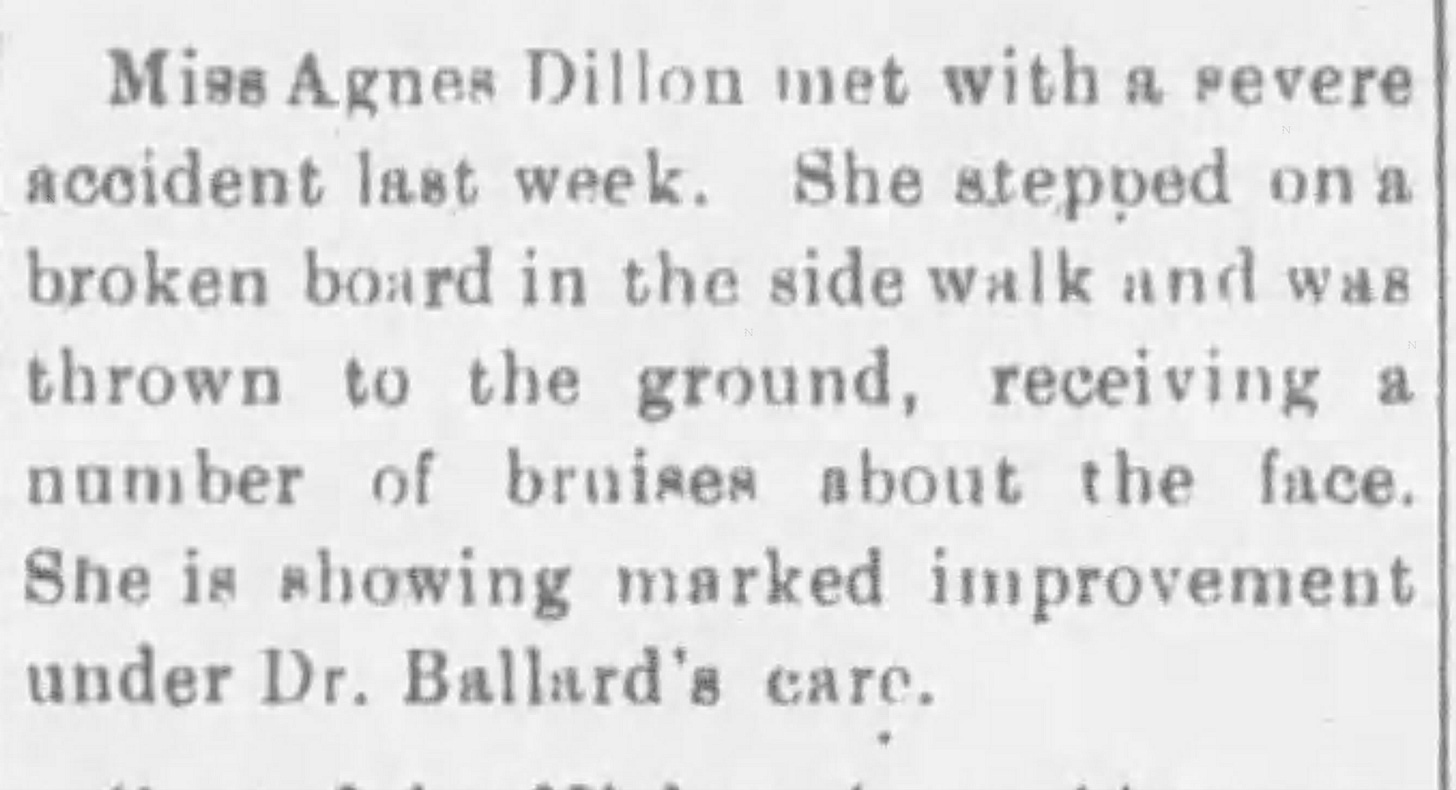

In 1900, Agnes lived with her parents and youngest sister Anne. On July 6 of 1900, the Chenoa Gazette reported Agnes’s encounter with a broken board in the sidewalk.

Agnes was educated as a teacher and held a position as the First Assistant to the Principal at Chenoa High School in 1900. By 1905, Agnes was Principal. According to the salaries listed in the paper in 1900, the male principal made $1000 per year. Five years later, when Agnes became the principal at the same school in 1905, she was paid $900 per year and this did not change over the next two years.

I wondered how/why Agnes wound up in South Dakota. She seemed fairly settled and was successful in her job with Chenoa High School. A small item in the September 18, 1908 Weekly Pantograph out of Bloomington, Illinois announced the scheduled departure of Agnes and her sister Anne later that month for Bonesteel, South Dakota to register for the upcoming “drawing of the land” from the Rosebud Reservation. The Rosebud Reservation belonged to the Lakota Sioux. Proclamation 820 was approved by Congress on March 2, 1907 and was subsequently signed by President Theodore Roosevelt. The proclamation declared that all lands south of the Big White River in specifically identified sections that “are not allotted to” Native Americans would be disposed of either by town site selection, homestead laws, and/or opened up for settlement and occupation. Roosevelt designated March 1, 1909 as the day the lands would be opened. The General Land Officer would furnish forms required for registration in various towns on designated dates. This was the purpose of the Dillon sisters trip north. Whether either sister obtained land that way, I don’t know, but it doesn’t appear so.

Agnes must have met John Makens at the registration or at least during her time in the area. The Bloomington Weekly Pantograph announced Agnes’s impending marriage to John which was to take place on May 21, 1909. Agnes was 45 and John was 52. In 1910, the couple and John’s six children with his first wife Catharine, who died in 1907, were living in Aberdeen, Brown County, significantly further north than Bonesteel.

Agnes appeared to have a good relationship with her step children: James, Mary Ann, Ellen (Nellie), Agnes, Winifred, and Adelaide. She is included in their life events, such as marriages and accomplishments, and they are named as her surviving children in her obituary.

Between 1910 and 1920, all of the Makens family but two pulled up sticks and moved to Hidalgo, Texas. After the move, in 1920, John was noted as a farmer and his property was mortgaged. He clearly had success because in 1930, the farm was owned free and clear and was valued at $35,000.

John Makens died at 75 on April 20, 1933 after a period of ill health. The obituary in the McAllen Daily stated that his wife was at home critically ill but did not give any details. The Valley Morning Star described John as a “McAllen Pioneer of the Rio Grand Valley” who settled in the town shortly after it was founded.

Whatever malady Agnes suffered from in 1933, she at least mostly recovered. In 1940, she was living with her sister Anne and her husband Leonard Humpfer who passed away in 1943.

Just before 6 a.m. on Sunday morning, March 10, 1947, a fire broke out in a bedroom of the McAllen home where 82-year-old Agnes, her 69 year-old-sister Anne Dillon Humpfer, their housekeeper, Bertha Hannah who was 60, lived. When the firemen arrived, Anne and Bertha had made it outside but Agnes was still inside. All three women had severe burns and were taken to the McAllen Municipal Hospital. Anne and Bertha recovered, but Agnes succumbed to her injuries the next day. Anne had received severe burns on her back, shoulders, hands, face, and neck, while Bertha’s were mainly on her hands and face. Fire Chief Ward Walters reported the source of the fire as a gas heating stove in a bedroom. The fire burned through the north side of the home and restarted itself several more times after being initially quelled. Chief Walters said this was caused by there being no gas shut-off and the water supply had to be brought in on trucks from Pharr which is a city running adjacent to McAllen. Agnes’s death certificate lists senility as one of her co-morbidities. This, combined with her age, may have contributed to difficulty for Anne and Bertha to get Agnes out of the home. (The death certificate misdates her birth by two years.) Anne lived to be 91, passing away in 1965.

I wondered how much influence Agnes had on the Makens children. With her education, experience as a high school teacher, and principal of a high school, she would have provided encouragement to them and it appears they each found and took the opportunities that came their way.

The eldest, James Makens, worked on his farm in South Dakota and moved to North Dakota by 1920 where he had a grain farm. He married Mary Catherine Coughlin and they had four children: Francis, James Jr., Agnus, and John. They moved back to South Dakota by 1930 and lived there until they died, James in 1975 and Mary in 1979.

Mary Ann Makens had a mind for business. She took a Commercial College Course in 1908. In 1930, she was a Clerk with the Hidalgo Irrigation Department, in 1940 she was the Hildaldo County Clerk. In 1950, she owned and operated the Monogram Stationers shop. Mary Ann never married which was stated in her obituary in the Monitor. It says she had taught school in Alaska and Panama in South America. Other credits to Mary Ann were the Secretary for Mercedes Commerce and Mercedes Tribune newspapers, and a charter member of Zonta Club. Zonta still exists as Zonta International. It is an organization of women who mentor and encourage young girls and women to recognize their rights as human rights and obtain their full potential. The Valley Morning Star named Mary Ann as one of the founders of the Business & Professional Women of McAllen, Texas. She died February 7, 1971 of multiple types of cancer.

Nellie Makens worked as a teacher in Kennewick, Washington situated on the banks of the Columbia River. The Oregonian newspaper announced her marriage to John Sullivan, a pharmacist in Washington state where they made their home together. They had four children: Agnes, John, Joan, and Thomas. Nellie died in Pasco, Washington in April of 1986 at 85.

Agnes married Ernest Hawley in McAllen, Texas in May of 1928. They spent a month in Colorado for their honeymoon and planned to return to their newly completed home on their acreage in south McAllen. Agnes was associated with the Retail Merchant Association for at least two years and was held in high esteem by coworkers.

Winifred was also a teacher. In 1919 she lived and taught in Tacoma, Washington. Like her sister Mary Ann, Winifred also taught in Panama. She’s included on a passenger list from Panama to New Orleans in July 1925. Her home at that time was in Pharr, Texas. In 1930, she married Captain Leo Alexander Bessette and made her home at Ft. George Meade in Maryland. They had one son, Eugene. She again was traveling in 1941. A passenger list includes her departing Port Au Prince, Haiti, arrivingNovember 15, 1941 in New York City aboard the Ancon. Leo Besette was a Colonel when he died in 1964 of a heart attack. Winifred died in 1986 at the age of 90 and is buried next to Leo in Arlington National Cemetery.

Adelaide initially remained in South Dakota when her family moved because she was attending Northern Normal and Industrial School, where she received her teaching degree in 1917. She taught in Aberdeen for one year. In, 1918, Adelaide enrolled in Trinity College in Washington, DC where she completed her Bachelors of Arts in 1920. She then moved on to George Washington University Law School and graduated with her law degree in 1924 when she then relocated to New York City to begin her law practice. She met and married Joseph Francis Reilly in 1927 in New York City’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral. On December 8, 1927 the couple returned to New York from Bermuda aboard the Fort Victoria and were noted as guests at the Commodore Hotel. After living in Bronxville, New York for a while, they moved to Houston, Texas. The couple had two children: Joseph Jr. and Stephanie. Adelaide was an active member of Community Council (now United Way), the League of Women Voters, and the University of St. Thomas Arts Board. She died in 1996 at the age of 99.

What a fascinating family. They certainly covered the country over the years.

An interesting family. Thomas Dillon's story is tragic.