Boatright Murder Trial: The Defense Begins

Part 6: The Buckfoot Gang

Attorney Francis D. Turner opened the case for the defense. Reiterating the claim of his client’s insanity, he started by telling the jury that some members of the Boatright family were subject to epilepsy and that Robert had lost much of his ‘native intelligence’ from an illness. Mr. Turner said Robert suffered a bout with typhoid when he was around 10-11 years old, and that his mind was “seriously affected” by it. He said Robert was kept closely confined at home in the years after that and had been recovering from the effects of the disease when Oscar was killed.

An objection was raised about this statement, the issue being that Robert was out prowling the streets with Oscar and several other boys when his brother was killed rather than being watched with a stern eye under home confinement.

The defense’s response was that Robert was ‘recovering’ and that’s why he was out and about, but he’d suddenly relapsed due to Oscar’s death, and this had caused him to show up at the courthouse and kill Charles Woodson in the courtroom. The prosecution rejected that explanation, saying Robert hadn’t dramatically ‘shown up’ at the courthouse, wild-eyed and wielding the knife, but had been calmly sitting in the courtroom audience when the trial started, having attended with his father who was a witness for the prosecution. If Robert was in the throes of an insanity relapse, I doubt his father would have brought him along to such an event and left him unattended.

If you’ve been following this story, you know the murder occurred after Robert had been sent out of the courthouse by his father, tasked with fetching a doctor to come to the courtroom for confirmation of his account of Oscar’s wounds. Robert used the opportunity to collect his knife, and it was when he re-entered the courtroom that he killed Charles.

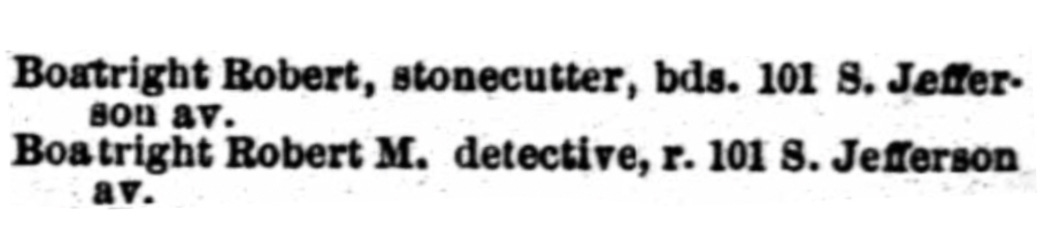

Attorney Turner said Robert had once worked for a stonecutter, which he is noted as doing in 1875, when he would have been 16. Turner said that after Robert finished his work, he would often destroy it. Mr. Turner also said Robert had attempted suicide twice, but gave no more information.

It was noticed by the journalists that it was never the defendant who spoke with his attorneys or prompted a question for a witness, but rather his father. For the time, I guess it isn’t really surprising since Robert was only 16-17 at the time of this trial and his father was far more familiar with courtroom settings having worked as a constable and a detective. Today, only the defendant would be seated with their attorneys.

The defense witness list was longer than I expected and was an odd assortment: two people from Franklin County where Robert had grown up, the publisher of Fireside Weekly, the western freight agent of the Ohio & Mississippi Railroad, and an employee of Fattman & Company, a planing mill for a furniture manufacturer. The intent of these witnesses was to prove the familial history of insanity.

First up was James Whitesett, a farmer from Franklin County who was acquainted with the family from their time living there. He said he knew a 25-year-old aunt of Robert’s who died in a fit, which she was prone to, and he felt Robert’s grandfather was “flighty or unbalanced in his mind at times.”

A.L. Bagwell was another witness who knew the Boatrights in Franklin County. He had worked for them as a farmhand in 1847 and made the acquaintance of Anne Boatright, who was a sister of the defendant’s father. This would have been the aunt James Whitesett referred to. Mr. Bagwell estimated Ann’s age to have been 17 or 18, but census records put her age at that time around 21. Not far off.

Mr. Bagwell said he knew Anne to be in poor health. When asked to explain, he said she regularly suffered from epileptic ‘fits’ at least every day and he’d heard of her having three in a day. He described her to have “no more mind than that of a child and a very small one at that.” I’ll leave out his vivid descriptions of the seizures which he went into much detail about. He said Anne died several years after that, but by then he had moved on. He did point out that he thought “the prisoner,” Robert P., resembled Anne, that he had the same complexion. Then commented that his father also had the same complexion.

On cross-examination, Mr. Bagwell said he was well-acquainted with Mr. Robert M. Boatright and that his mind was sound as anyone else’s and he considered him sane. Thank goodness for that.

The next few witnesses had been neighbors of the Boatright family and testified to Robert’s behavior when he was younger. Joseph Miller had known the family for roughly nine years and were next-door neighbors. He said Robert was “quiet, intelligent, clean, orderly, and obedient” until his illness.

Henry Tice took the stand and promptly divulged to the court that he was brother to Professor Tice. Presumably, this was John H. Tice who was what we would today call a Meteorologist. In the late 19th century, Professor Tice published books on cyclones, weather forecasting, geological information, and an almanac.

Mr. Henry Tice said that over the seven years he knew the family, Robert P. would come over every day to play with his own boys and was very bright, intelligent, neat, orderly, and was smart but pointed out that he never saw the boy take a particular interest in books.

On cross, Mr. Tice said he felt he had been fairly well-acquainted with the defendant while they lived in the same neighborhood until two years prior when they moved. During that two-year period, he said he had seen Robert a couple of times but did not converse with him. He described him as appearing “downcast and without any mind.” He elaborated that Robert’s mind seemed to be on something else and that he was certain if Robert hadn’t been preoccupied he would have seen him and spoke.

After re-direct and re-cross examination, it was clarified that when Mr. Tice saw Robert P. those two times it was in the Boatright home. Mr. Tice was in the parlor speaking with Priscilla Boatright when Robert came in from outside. He felt that the boy failing to stop and speak to him was abnormal.

Mrs. Matilda Tice, wife of Mr. Henry T., confirmed that the Tices and Boatrights were close neighbors. Robert had always seemed bright, mannerly, and affectionate, being friendly with the Tices and their children up until he contracted typhoid. Unlike her husband, she recalled seeing Robert being “lively with his books” and knew from his parents that his teachers had praised him. She agreed with her husband that Robert was not the same after his illness.

Matilda Tice said on cross-examination that she had seen Robert three times since he had been sick. Once she saw him on Christy Avenue (the family lived on Christy from 1872-1874) and stopped to ask after his mother. She said he stared at her like he didn’t know her and didn’t answer. Another time, she was at the Boatright home visiting Priscilla when Robert came into the house. His mother asked Robert if he remembered Matilda Tice. She said he smiled but didn’t reply. The third time, she came upon Robert and other boys outside playing marbles and she asked him where his mother was. He didn’t give her an answer. She then said, “He was just as wild as before.” Whatever that means. I don’t consider playing a game of marbles to be wild, but perhaps she did.

This collective of observations certainly could be indicative of a major change in personality. Conversely, since it had been some time since Robert had interacted with the Tice’s, at least some of it could be due to Robert’s age, a boy of 11 at the time. It might have been an awkward age for Robert, illness or not, and he might have worried about what his buddies thought of him. These examples also detract from the defense’s statement that after his illness, Robert was confined at home and closely monitored. Nothing indicates he had been.

Bryson Truesdale testified that he’d known the Boatrights since 1869, (Robert would have been 10), when he lived in the same apartment building as them for one year. He again describes Robert as bright, gentlemanly, neat, active, and quiet. He said he knew Robert was sick during the winter of 1869-70, that he’d been feverish, and “talked out of his mind.” Mr. Truesdale moved away in March of 1870 but had seen Robert twice since then. He bluntly said he felt he was “more stupid than he used to be” and “he was stupefied when he was getting over his illness.”

Mr. E.O. Pickering, a former member of a by-then disbanded St. Louis militia that called themselves the ‘Mackerel Brigade,’ said he had known Robert for six years. Robert’s father had been a member, serving as an adjutant. Mr. Pickering noted the defendant “always associated with younger and smaller boys, cut up peculiar antics, and would throw his heels over his head and laugh idiotically.” Mr. Pickering said he talked to the boy on the day his brother, Oscar, was buried telling him “you must be an ornament to your family now that you are the only child left to your mother and father.” He didn’t feel Robert took much notice of what he said and saw him “throw some mud at a sign.” He then stated, “I always thought he was an imbecile,” and “never knew him to do a sensible act in his life.”

On cross-examination, Mr. Pickering revealed he had actually known Robert in 1867-68; he would have been 8-9 years old. He went on to say that, “Previous to his illness, I paid no attention to him. When he saw the old lady coming, after he struck the sign, he ran.” When asked what he meant, Mr. Pickering explained to the prosecuting attorney that he, himself, had broken a lot of windows when he was a boy and, “I would have run if I had been in the boy’s place too.”

So yeah, I’m making judgements, based on my opinion, about what some of these witnesses testified. They were called as witnesses to portray insanity in Robert. Maybe the testimony often is not being conveyed well in the newspaper, which is highly likely, but overall, it doesn’t seem like such egregious behavior for a boy of 8 to 12 years old that it would indicate insanity. I’m not sure what point Mr. Pickering was trying to illustrate by comparing Robert throwing mud at a sign after Mr Pickering had just advised him to be “an ornament” to his own personal history of breaking people’s windows as a boy.

I don’t think Robert was insane. It would be to his benefit if he was, but I really don’t believe that. I think he knew full well what he was doing. Of course, I have the benefit of hindsight, the story of which will unfold as this series goes along.

There are more defense witnesses to come in the next installment.

I always knew those Boatrights were a shady bunch!!!! lol

What great insight into the legal defense for mental illness of the day! I know epilepsy was often seen as a sign of insanity or even possession, but some of what is described just seems like grumpy old folks yelling “get off my lawn” to a boy who was maybe slowed down by illness and his life situations.

Great research and storytelling, as always. Can’t wait to hear more witnesses!