Continuing the biographical vignettes of the ladies who signed an 1882 Autograph book I found at a flea market. The young women were classmates at St. Mary’s Academy, an elite boarding school for girls on the campus of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana. If you missed it, the first installment can be found here: What's in a Name?

When I started writing this series about the ladies from the St. Mary’s Academy class of 1882 , I had no idea who the autograph book originally belonged to. I could only take a guess and wonder if the signature on the first page, which was somewhat brief compared with others, was the owner. I don’t believe she was because I found a wonderful clue on one of the pages.

I’ve been writing about the lives of each lady as I go through the book, page by page. When I finished the post about Katherine Donnelly, I went to the next. That person (whose story will come after this one) not only signed her name and home location, but wrote a three-stanza poem in French. I saw it when I initially looked through the book, but had not yet translated it, so I hadn’t read it closely. When I did, I was pleasantly surprised by the gift this woman had given me. She addressed the owner of the book by name! The first line of poem is, “Childhood, my dear. Carrie, should it always be.”

Am I 100% certain? No, I can’t be really, but this is an autograph book and this is all there is. A signer addressing someone by name is a pretty darned good clue. In favor of identifying the owner, there was only one Carrie associated with the 1882 class at St. Mary’s. Caroline ‘Carrie’ Louisa Hock Gall.

Carrie was elusive, not only because she didn’t record her name in her book, but her surname was changed sometime after she turned eight years old. Let me explain…

Fredrick Hock was born in Würtemburg, Germany in 1826. Frederika Wilhelmina Correll was born in Bavaria June 30, 1845. Both families emigrated to this country and settled in Memphis, Tennessee. Fred, as he was familiarly known, married Frederika on September 4, 1858 in Memphis. Their marriage certificate is below.

It still amazes me when an official document is completed with only the initial of one or more persons rather than their full name. All the names, even the witnesses, are written out except Frederika’s, the actual bride.

Fred was a druggist with his own shop, Hock & Company, at the corner of Greenlaw and Second in downtown Memphis. In 1867, a Dr. Ferdinand Saupe, Physician, is listed as being in business at Hock & Co. Whether this was as a druggist, an investor, or the building was the location of his clinical office, it doesn’t specify. In addition to the ordinary stock, Hock & Co. also offered guitar strings, portemonnaies (wallets), and Catawba wine. However, the year 1867 was the last for Hock & Company.

On the 20th of March, 1867, Fred Hock and a man named John C. Nagel filed a statement confirming they were indebted to A. Gruber (not listed in Memphis) and Valentine Driessigacker (owner of the Monroe Exchange Saloon at 38 Monroe) in the amount of $250.00. I don’t what Fred’s business relationship with John Nagel was. Nagel owned a saloon at 186 Main; Fred Hock’s residence was 184 Main. Maybe they went in together to make purchases for their respective businesses.

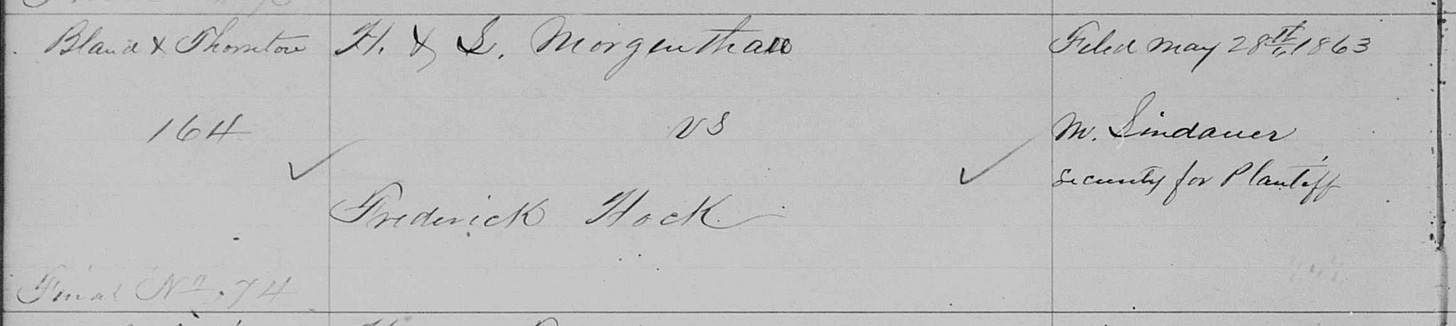

In the first week of March, 1868, Fred filed a petition of bankruptcy. The 1867 suit wasn’t the first time Fred had financial troubles. In 1863, he was sued by Lewis Morganthau for the cost of the purchase and delivery of ten boxes of Rhine wine.

The petition specified $57.50 for the cost of the wine, with drayage and interest being added to that. The totaled amount of $62.30 was reduced to $54.18, $3.32 less than the product cost. The amount of $3.32 happens to be the difference between the interest and the drayage. I’m not sure how or why they did that math. Mr. Morganthau also sued for $250.00 for filing the suit. The court ignored the plaintiff’s ambitiousness. The judgement was that Fred would pay $54.18 for the product, $3.25 for interest, $10.90 for the costs of the lawsuit, and $10.00 for the expenses of the Commission. The judgement came to $78.33. On June 10, 1863, Fred Hock paid the $78.33 and the suit was satisfied.

Undoubtedly contributing to his woes, Frederick was not a well man. On December 3, 1868, he died of tuberculosis. He was a member of the Leila Scott Lodge of the Masons, and on December 6, the lodge placed an announcement in the Memphis Daily Appeal newspaper of a meeting at the Masonic Hall in honor of their deceased brother, Frederick Hock.

Fred did have a will. Dated November 28, 1868, the will states Fred had a life insurance policy through Globe Mutual Life Insurance in the amount of $5,000 payable upon his death to his wife Frederika and their three children, whom he thankfully named: Emma, Caroline, and Eleanor. He designated $4,000 to be used in lieu of dower to purchase real estate in Frederika’s name, and she was to have full use of the property during her natural life. After her death it was to go to the children in proportions they could agree upon. The remaining $1,000 plus all other assets of his estate were to go to Frederika and the girls in common. He appointed Frederika as sole executrix of the estate.

Frederika’s father, Laurence Correll, died in 1869. He owned and ran a restaurant and saloon in Memphis. When Laurence died, his wife Margaretha took over and ran the business for years. In 1870, Frederika and her daughters Emma 10, Caroline 7, and Eleanor 6, are living with Margaretha along with Frederika’s four youngest brothers. The life insurance money must not have been absorbed by the bankruptcy because on that census, Frederika’s personal real estate value was listed as $6,000.

It would have been very shortly after this census that Caroline, commonly called ‘Carrie,’ would be sent to live with relatives in Indianapolis, Indiana. Her new home was with her aunt, Caroline Elizabeth Gall, née Hock, widow of Dr. Alois Dominikus Gall.

Based on several references to their family relationship, I know Caroline and Alois were Carrie’s aunt and uncle, with Caroline being her blood relative. The best I can work out is that Caroline Hock was probably a sister of Carrie’s father, Frederick. The young Carrie was baptized on February 18, 1868 and “Frau Caroline Gall” was the witness/godmother.

Caroline Elizabeth Hock was born in 1818 in Paris, France “of German parents.” When Caroline was 5-6 years old, so aound 1823-1824, the family relocated to Germany. The timing would be right for Frederick as a younger brother; this is where Frederick was born in 1826.

Caroline married Alois Gall in Germany and in 1842, they emigrated to the U.S. They initially lived in Green Bay, Wisconsin, and for a short time in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania before permanently settling in Indianapolis. The obituary mentioned there were a few years between 1857 and 1861, where Caroline lived in Antwerp while Alois was “the consul at that place.” During the Civil War, Dr. Gall was surgeon for the 13th Indiana regiment.

A later obituary states that Carrie was Caroline’s niece, was born in Memphis in 1863, and lived with the Mrs. Gall since the age of eight. Alois died in 1867, before Carrie came to Indianapolis, so she may never have known him or had been too young to remember him.

Whether Carrie’s surname was changed immediately upon her move to Indy or sometime after, I don’t know, but I’ve seen nothing at all with the surname Hock used for Carrie after 1870. The name change may have been done legally, but I haven’t found any legal documents or guardianship paperwork regarding Carrie. Requirements for name changes then were certainly not what they are today. This move appears to have been an intentionally permanent one, as when a godmother is assuming the care of a child who will be as her own. So, a surname change makes sense.

Caroline Gall was very well off. The Gall homes were in the northern part of Indianapolis, on the streets of Delaware and Meridian, roughly at the southern edge of the Old Northside neighborhood. None of their houses for which I found addresses have survived. Only those a little further north than the Gall address still stand.

The 1880 census shows Carrie as a student at St. Mary’s Academy. An account of the commencement was printed in the paper, but unlike other years, this one omitted the names of students receiving awards. Since Carrie was not mentioned as part of the performance, I don’t know if she received an award or not.

In the years following her graduation from St. Mary’s, Carrie is a society page frequent flyer. Her involvement in civic organizations is often reported upon. A list of organizations she was involved in would be quite long, so here are a few brief examples:

The Citizen’s Fair. Carrie gave a recitation at a benefit for the Sister’s of Charity Infirmary.

The Lyra Society Annual Festival. A costume dinner was given to raise money. Carried was dressed to represent Spain.

The Flower Mission Fair. Carried worked a booth to raise money for the group’s purpose of delivering flowers, fresh fruit, and reading material to hospital patients. She was a member of this group until she died.

A Parlor Concert given by the First English Lutheran Church’s Ladies’ Society was held at the home of “Mrs. Dr. Gall.” There were instrumental and vocal performances by the Philharmonic Orchestra, recitations, and Carrie read a paper describing the objective of the organization.

On the purely social side, in July of 1885, Carrie and her friend Addie Brown held a progressive euchre party. The card-playing guests changed tables and partners after each round to encourage making new friends. Clearly, one goal of the party was for eligible ladies and men to meet. At this event, the gentlemen invited did not show up as “the tall girls with ribbons on their arms were forced to do the duties of the missed and wished-for gentlemen.” One young women who attended said “…if only we could see some real live men.”

I want to remark on a “Café” given by Carrie’s cousins. Mrs. Albert Gall (Bertha) and Mrs. Fred Rush (also named Carrie) gave a café at their North Meridian Street home. The invitations said, “Bring your knitting.” I’m a knitter, so I’m already 100% down for this. The report says nearly every guest brought knitting, crocheting, or some type of handwork. Several of the guests were named, and yes, there were men in attendance. Food, knitting, and friendship…that’s my kind of luncheon.

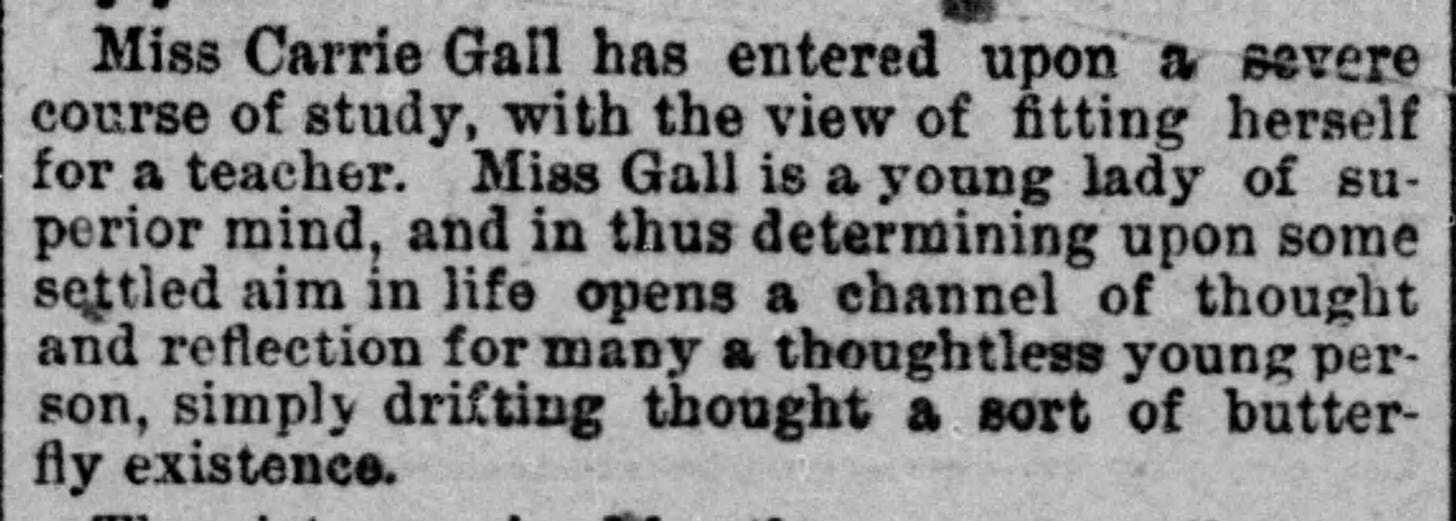

In March of 1885, Carrie enrolled in what the Indianapolis Journal called “a severe course of study.” Carrie wanted to be a teacher. In February of 1886, she’s listed as the German language teacher at a local school. Having grown up in a family of German immigrants, she may have already been fluent in German and wanted the education certification in order to work as a teacher.

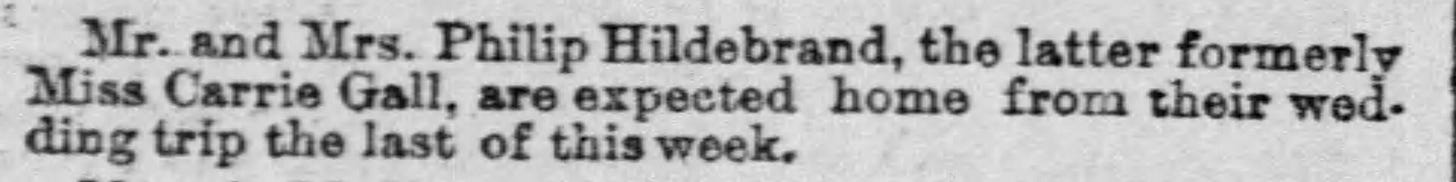

In April of 1887, Carrie’s engagement to Philip Hildebrand was announced. Philip was born in Pennsylvania on June 19, 1851. The couple was married on the evening of November 23, 1887 at the First English Lutheran Church. Carrie’s gown was of dazzling white silk “en train,” adorned with orange blossoms. A supper was held for thirty-five relatives and friends in the home of her cousin Albert. Philip’s gift to Carrie was a set of diamond solitaire earrings. The couple left for a honeymoon “as far south as Florida.” They were expected to return around the third week in December.

When Carrie marred Philip, he was a junior partner in Hildebrand & Fugate. His father, Jacob Hildebrand, moved his family from their birthplace of Adams County, Pennsylvania to Indianapolis in 1854 and began working in John Vajen’s hardware business. In 1860 Jacob became a partner, and bought out Mr. Vajen in 1870. The company then became Hildebrand Hardware and later was renamed Indianapolis Hardware with Philip as Vice President. Philip was also an investor in mining companies and various businesses in the city.

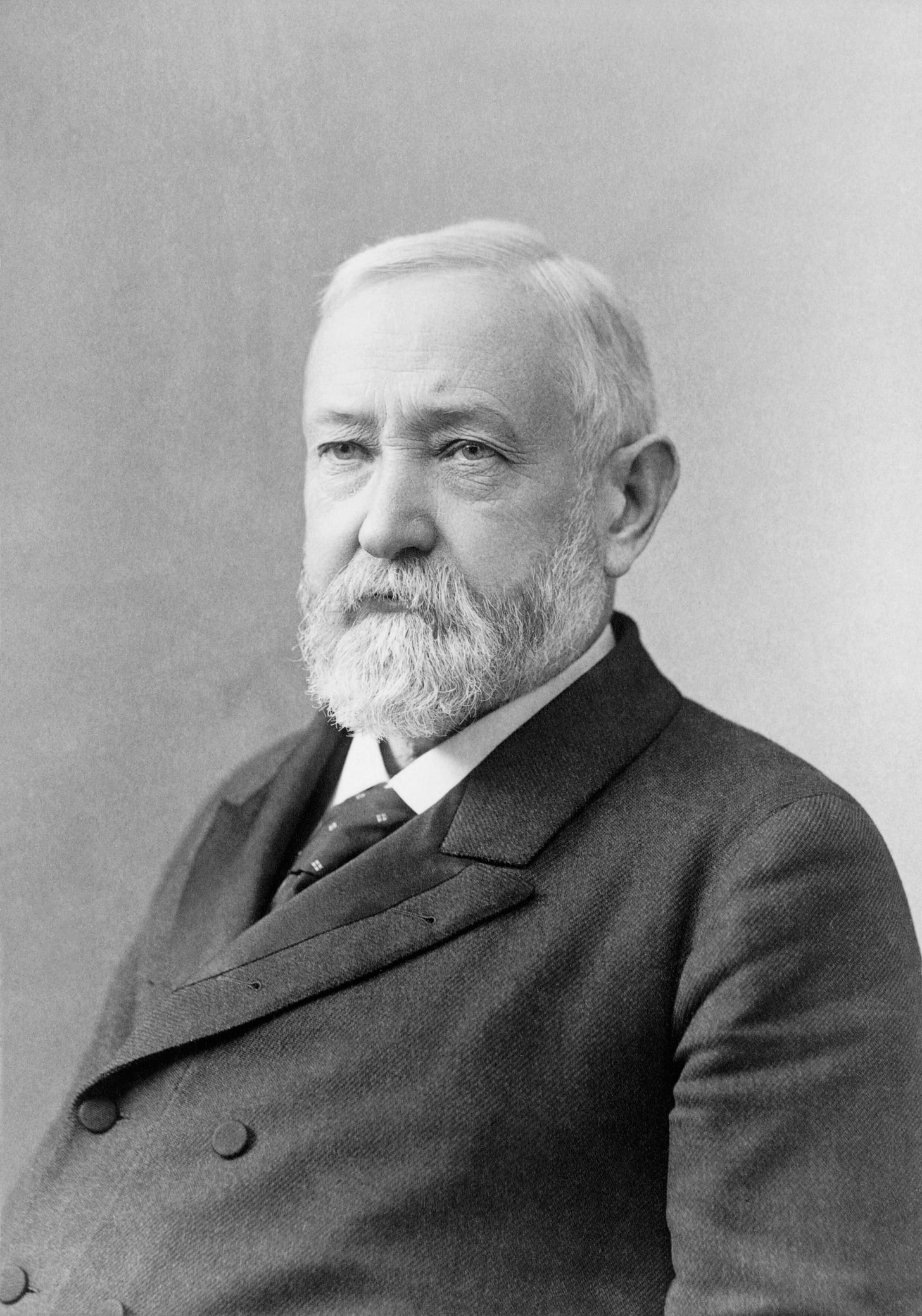

In 1889, President Benjamin Harrison, who was from Indianapolis and is buried there, appointed Philip as Surveyor of Customs and Collector of Internal Revenue for the port of Indianapolis. Designating Indianapolis as a ‘port’ sounds ambitious and was mainly wishful thinking. Indy is land-locked and completely inaccessible to ocean-going vessels, but the White River does run through the city and was a well-used route for the transport of goods. The Indiana Central Canal was a project intended to connect the Wabash & Erie Canal to the Ohio River, but it was never completed.

Philip had plenty of backing from local merchants, importers, and organizations, but as with most politically influenced appointments, in September of 1893, newspapers reported that the Secretary of the Treasury was calling for Philip’s resignation. His term was due to end on January 30, 1894, so why such a kerfuffle was being made with only four months to go, who knows. Philip vacated the position on December 1, 1893, when a George Tanner assumed the office. Cause for requesting his resignation was never given even though the Treasury office was asked numerous times. The melodrama of calling for him to resign may have been performative, not unusual even today. Philip was either forced out with only two months remaining for reasons the Treasurer wasn’t willing to divulge or he merely got fed up with the histrionics and stepped down. I can’t blame him.

At least on paper, Philip remained actively employed in 1930 when he was within two months of his 79th birthday. He is cited as a “Commercial Traveler” for Tokheim Oil Tank & Pump Company. The company made some of the earliest gas pumps.

Documentation for some of the ladies I’ve researched drops off steeply after their marriage, which often meant moving away from family, an unfamiliar location, new responsibilities, and time being consumed by the quick and frequent arrival of children. Not so for Carrie. Her name, and Philip’s as well, still frequents the society pages, appearing every few days during the social season. Progressive euchre parties were still the rage in 1890 and Carrie hosted one for fifty people. She held a coffee for thirty of “her German friends” one day, and three days later a coffee for “her American friends.” Carrie and Philip hosted a driving party with supper in the country.

Carrie and Philip had three children: Caroline Louise born 1888, Lydia Ann born 1890, and Philip Sheffield born 1892. Their children would have been pretty young at this time, and it seems like a monumental task to pull off these types of parties. They may have had household help, but I’ve not seen mention of it, although nannies weren’t necessarily fodder for the society pages. No servants are listed on the 1900 census for the Hildebrands, not until 1910 when their youngest was 17 and childcare would not be needed.

Carrie was a member of the German Literary Club which met in members’ homes and presented programs every two weeks. Mrs. Bernard Vonnegut (Nannie Schnull, grandmother of author Kurt Vonnegut) and Mrs. Clemens Vonnegut (Katarina Blank, great-grandmother of the author) were also members. In 1896, the club’s calendar events were published. The two Mrs. Vonnegut’s were included in those responsible for presenting "Begruendung des Deutchen Reiches” (Founding of the German Empire) in November, Mrs. B. Vonnegut for "Weihnachts im Walde” (Christmas in the Forest) in early December, and Carrie for “Vermaechtnisse des Nordens” (Legacies of the North) in late December.

A local newspaper lamented the fading away of the old custom of Open House, the annual reception of friends into your home on New Years Day. On January 1 of 1895, there was a revival of the custom and the newspaper printed a list of the families who participated which included the Hildebrands. The ladies’ gowns were described as breath-taking, made of organza, velvet, satin, silk, and laces. I’d love to see a photo, or even a drawing, of this because I just know the Hildebrand house would have been decorated to the nines. This schedule of social events continues with regularity through the early 1900s.

Caroline Elizabeth Hock Gall, Carrie’s cherished aunt and namesake, died on April 5, 1889 at 71 years old. Over the years, Carrie kept in touch with at least some of her family in Memphis. In September of 1893, the social page reports Carrie’s sister, Eleanor Werner, visiting the Hildebrands at their 1925 North Meridian Street home, which has now been replaced by modern buildings.

Philip Miller Hildebrand died of heart disease at 88 years of age on December 29, 1939 at his and Carrie’s home on Winthrop Avenue in Indianapolis.

Caroline ‘Carrie’ Louisa Hock Gall had a long and active life. In March of 1945, she was elected President of Chapter Q of the Philanthropic Educational Organization Sisterhood, as well as being chosen as their delegate to the state convention, but was unable to act in that office for very long. She was a determined, strong woman who persisted in the work of the organizations she believed in, even through her last illness. She passed away at 82 in her Winthrop Avenue home a month later on April 23, 1945, from breast, lung, and stomach cancer.

Carrie’s obituary recounts her birthplace as Memphis and that she came to Indianapolis at eight years of age to live with her aunt Caroline Gall. Her time at St. Mary’s is noted, as well as her graduation from Mrs. Nicholson’s Teachers’ School.

She was noted as a German teacher in the city public school system, a lifelong member of the First Evangelical Lutheran Church, an active member of War Mothers of World War I, the Flower Mission, and the Propylaeum. The Propylaeum is an organization founded in 1888 by May Wright Sewall. Her purpose was to enhance women’s active role in society, to expand women’s opportunities for higher education, and was solidly on the side of women obtaining the vote. The Schmidt-Schaf House at 1410 N. Meridian has been the home of the organization since 1923, after their original building was purchased by the city for the World War Memorial Plaza. The Memorial is still located there in the Obelisk Square block.

Carrie is buried in Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis, as are most of the Gall and Hildebrand family members.

Carrie’s eldest child, Caroline Louise Hildebrand, became a Doctor of Chiropractic. She married Eugene H. Milleson on June 4, 1913, but they divorced between 1940 and 1950. They had three children. Caroline was still working hard in 1950 at age 61. She owned and operated a chiropractic clinic and is noted as having worked 75 hours in the week previous to the enumeration. Caroline died on May 29, 1962 of heart disease at 73.

Lydia Ann Hildebrand obtained her BS from Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana in June of 1913. In April of that year, she was elected Queen of the May by a majority of 488 votes over seventeen other candidates. She was a member of the Purdue Girls’ Club, Purdue YWCA, Purdue Glee Club, the Philomathean Literary Society, and the Progressive Club. She had been on the staff of the Purdue Exponent, a daily newsletter, and was currently the editor of that publication.

Lydia worked as a teacher with a specialty in child development and parent education. She taught in the Indianapolis school system as her mother had. She spent 1928 at the Universities of Minnesota and California as a national fellow in child development under the Laura Spelman Rockefeller fund and subsequently taught at Michigan State. In 1940, she lived in Washington, DC and worked as an educator for the Department of Agriculture until her retirement. Lydia seems to have enjoyed travel. She is included on passenger lists returning from France, Hawaii, and other distant places.

Lydia married Charles Lynde on June 30, 1915, but he passed away between 1921 and 1923. They had two children. Due to heart disease and diabetes, Lydia Ann died on November 6, 1976 at 86 in her home in Falls Church, Virginia.

Philip Sheffield Hildebrand graduated with the class of June, 1911 from Shortridge High School. Like his sister Lydia, he graduated from Purdue University. He served in WWI and after returning home, moved to Oregon to work in the timber business. While there, he married Mary Elizabeth Fares on May 15, 1920. They had a son on September 23, 1921, Philip Sheffield, Jr. The Hildebrands continued to live in Oregon for several years. In 1927, Mary is listed in the Motor Vehicle Registrations as driving a Dodge Roadster, so something like this.

On June 15, 1923, during what may have been a visit to Mary’s family in Middletown, Ohio, at only twenty months old, Philip Jr. passed away in Butler County, Ohio. His cause of death was convulsions secondary to whooping cough. Philip and Mary had no other children.

By 1930, the couple was back in Indianapolis where they stayed for the rest of their lives. Philip worked for Indianapolis Belting & Supply Company for 40 years. He retired sometime after 1950. In 1940, Mary had returned to teaching and was employed in a private school kindergarten, but had retired by 1950. Philip died January 18, 1963 at 70 years old. His obituary says he suffered a fatal heart attack while working in his yard. Mary died in 1977 in Ohio.

Carrie Hock Gall is my best guess to the owner of the autograph book, and the only one backed up by evidence of any sort. I feel fairly confident she was the owner. There is something magical about reaching back through 143 years and momentarily making contact with a young lady whose strength emanates from the documents that remain. Her sparkle is clear in the photo of her used for her obituary. What better way to convey her spirit. We can never know all the ups and downs of anyone’s life, but we do know that Carrie thrived and worked to make a better life for herself and those around her.

Wow, it just sends a tingling down my spine. What remarkable women. I often wonder if there's anything we do that can be as significant.

Cynthia, As you know, I love this series! Great research to find the owner of the book. I wonder who gave it away. Re Euchre, I played that when I was in college in the 70s at UE in the Indian ( the snack shop and meeting place in the Student Union Building). Now, you brought back that memory for me! Thanks. Again, great series!