If you would like to start from the beginning, this series starts here: In the Beginning: Part 1 The Buckfoot Gang

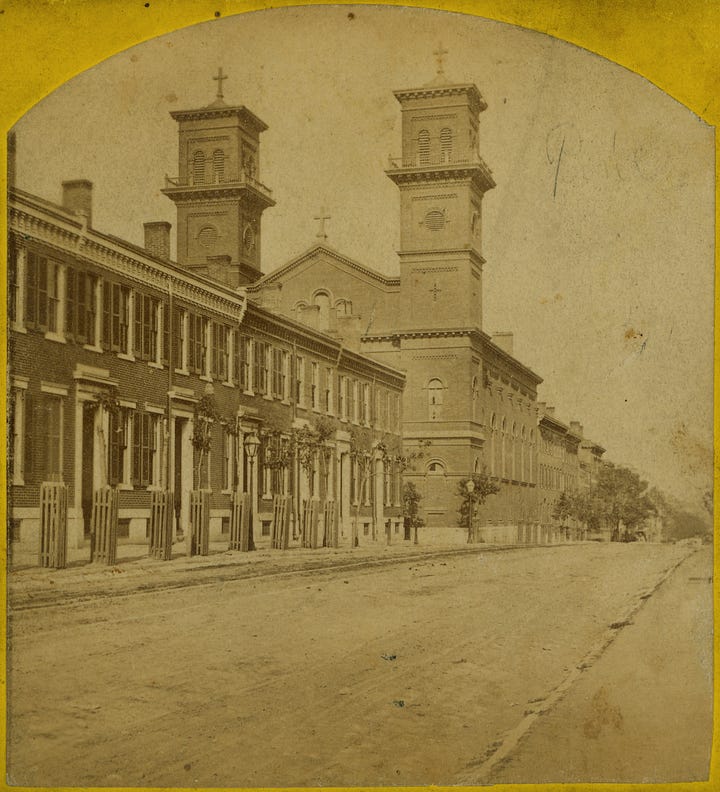

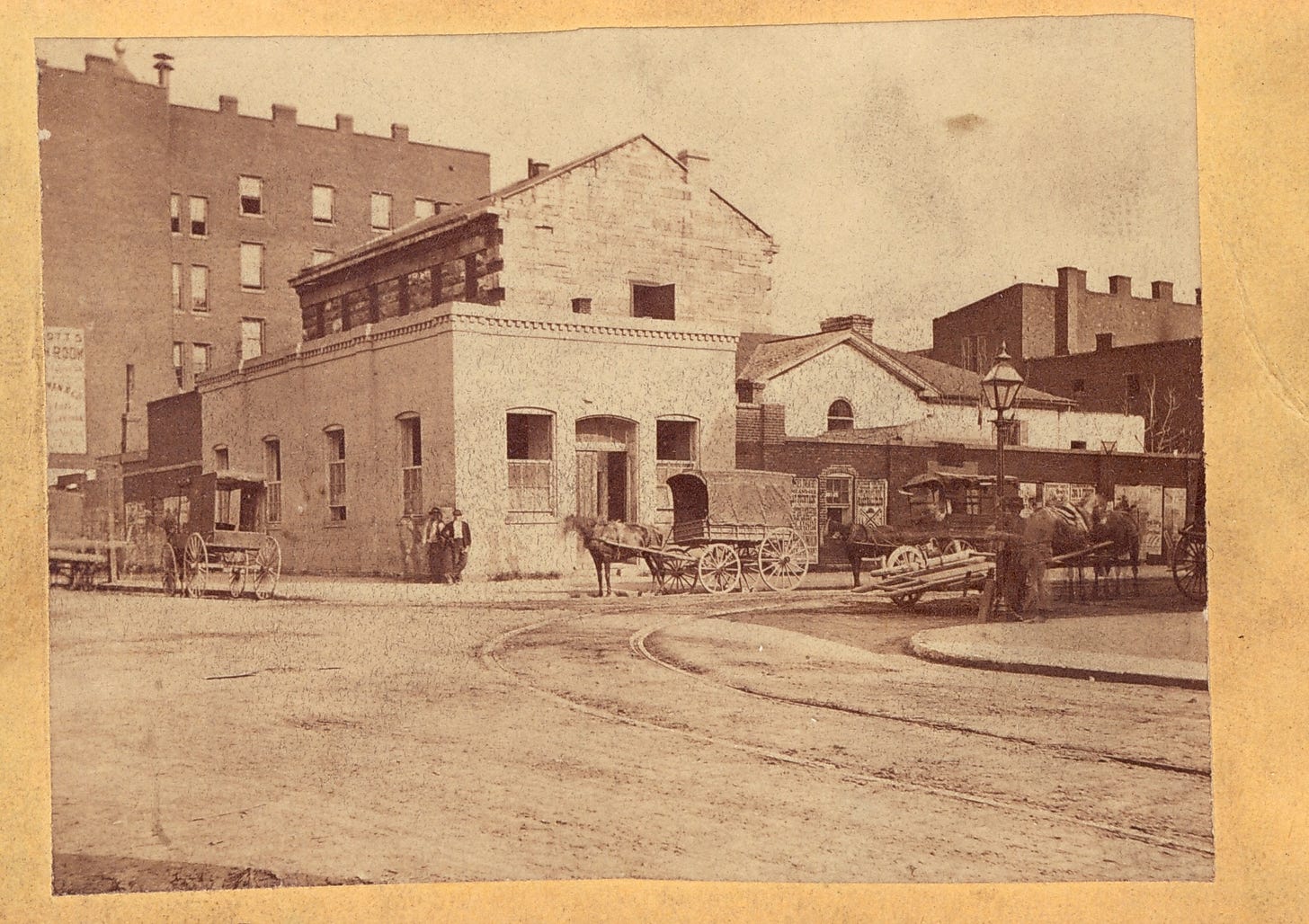

No bail for you! Judge Lindley made no bones about it. After the new not guilty plea, the judge was in a sour mood. Robert Boatright was hauled back across the street to the city jail.

Nothing was said about Robert’s reaction to any of the proceedings other than he “appeared unconcerned.” He’d been back in the nick for barely a month when the papers were abuzz with news of an attempted jailbreak, calling it a “well-planned scheme for carrying aid and comfort to the prisoner.”

Arrested was Benjamin Franklin Sloan for smuggling a knife and saw into the jail secreted in a dish of peas. What immediately struck me about this is that Sloan was the maiden name of Robert’s mother, Priscilla. Priscilla had a brother named Benjamin Franklin Sloan and records show there was a young man of the same name who was within a year of the same age as Robert. I haven’t yet found positive documentation linking them together, but it appears this Benjamin was likely Priscilla Boatright’s nephew, her brother’s son.

In the pokey along with Robert Boatright was Robert J. Rittenhouse. He was a seasoned criminal recaptured in Texas after more than a year of freedom after breaking out of the same jail in which he now sat. He’d been imprisoned as a counterfeiter in the McCartney gang. (I’m a little curious about this because McCartney is another of my family names from the same time and across the Mississippi in Illinois. Sigh, another rabbit hole.) Now that Rittenhouse, aka Joe Brown (clever), was back in jail, it was noticed by the guards that he and Robert Boatright had struck up a friendship. They spent their exercise time together, murmuring to each other and looking around. This dodgy behavior by Robert is an about-face from what was observed prior to his first trial. The guards were concerned and were watching them.

On later reflection, some thought Rittenhouse had observed the willingness of others to help Boatright and thought he might gain some benefit from assisting Robert by once again escaping along with him.

At 11 a.m. on June 18, 1876, a teenaged boy named Benjamin Sloan popped into the jailers office with a basket of food for Robert. He’d done this several times before, so it wasn’t unusual. He told the guard he’d been sent by Robert’s mother, Priscilla Boatright. There it is.

Deputy Turnkey Jeremiah Coakley recalled that when Benjamin delivered meals to Robert, he would come into the office, announce himself, and wait while Coakley brought Boatright out to talk with him. Coakley said Benjamin would remain in the office as long as the guard would permit. This time, when Coakley said he’d go get Robert, Benjamin said he was in a hurry and left.

Coakley was aware of the connection between Boatright and Rittenhouse and with the change in Benjamin’s behavior that day, decided it would be a good idea to check the basket. There was nothing hidden beneath the dish, so he stirred the peas. From the bottom of the dish, Coakley removed a small bundle wrapped in muslin. Inside was a knife and small saw. Coakley rang the jail alarm bell, then he and another officer immediately set after Benjamin who, at the time, was said to be found blithely strolling along 12th Street. Later, Coakley described it a bit differently. Benjamin was either unaware of the items hidden in the food or he was cool as a cucumber. Knowing this bunch, I suspect he was chill. He denied any knowledge of the hidden items and said he’d merely accepted the hamper from the hands of Priscilla Boatright to bring to Robert as he had done before.

The dish must have been fairly deep, like a casserole dish, because the knife was described as 6-inches long (a family favorite apparently) and a saw that was capable of sawing through bars. The knife was meant for the guard.

I don’t know how this happens. Robert’s case was docketed for November 20 in front of Judge Jones. Jones had deferred the case to Judge Lindley back in Circuit Court to accommodate Attorney Beach’s schedule. On the scheduled date, the prisoner, his attorneys Turner and Reed, and his parents appeared before Judge Lindley, but the court quickly discovered a full jury had not been empaneled and there was no prosecuting attorney present. Attorney Beach didn’t show up. This is the second no show at court, this time by the prosecution.

Defense Atty. Turner explained he had notified Atty. Normile the defense would be ready to proceed with trial on the scheduled date and Atty. Normile had replied the prosecute was also ready and confirmed that Atty. Lewis B. Beach would conduct the case. Failure to appear was not a good look for Mr. Beach’s first criminal case.

Justifiably irritated and angry, the judge said he would continue the trial one time but if the prosecution didn’t “take some action” or show up, he would enter a nolle prosequi in favor of the defendant. (Nolle prosequi - Latin for ‘not to wish to prosecute.’) Basically, he’d dismiss the case. He said he would write to the Attorney General to notify him this might happen and also ordered the Governor of Missouri be notified. Judge Lindley was done messing around.

Having corralled all the attorneys, the trial began on December 19, 1876. In one day, the jury was empaneled, the prosecution presented its case and the defense began theirs. Even the newspapers printed various versions of, “we’ve talked about the details of this case so much that there’s no need to repeat it.” Even so, the trial still attracted crowds of spectators.

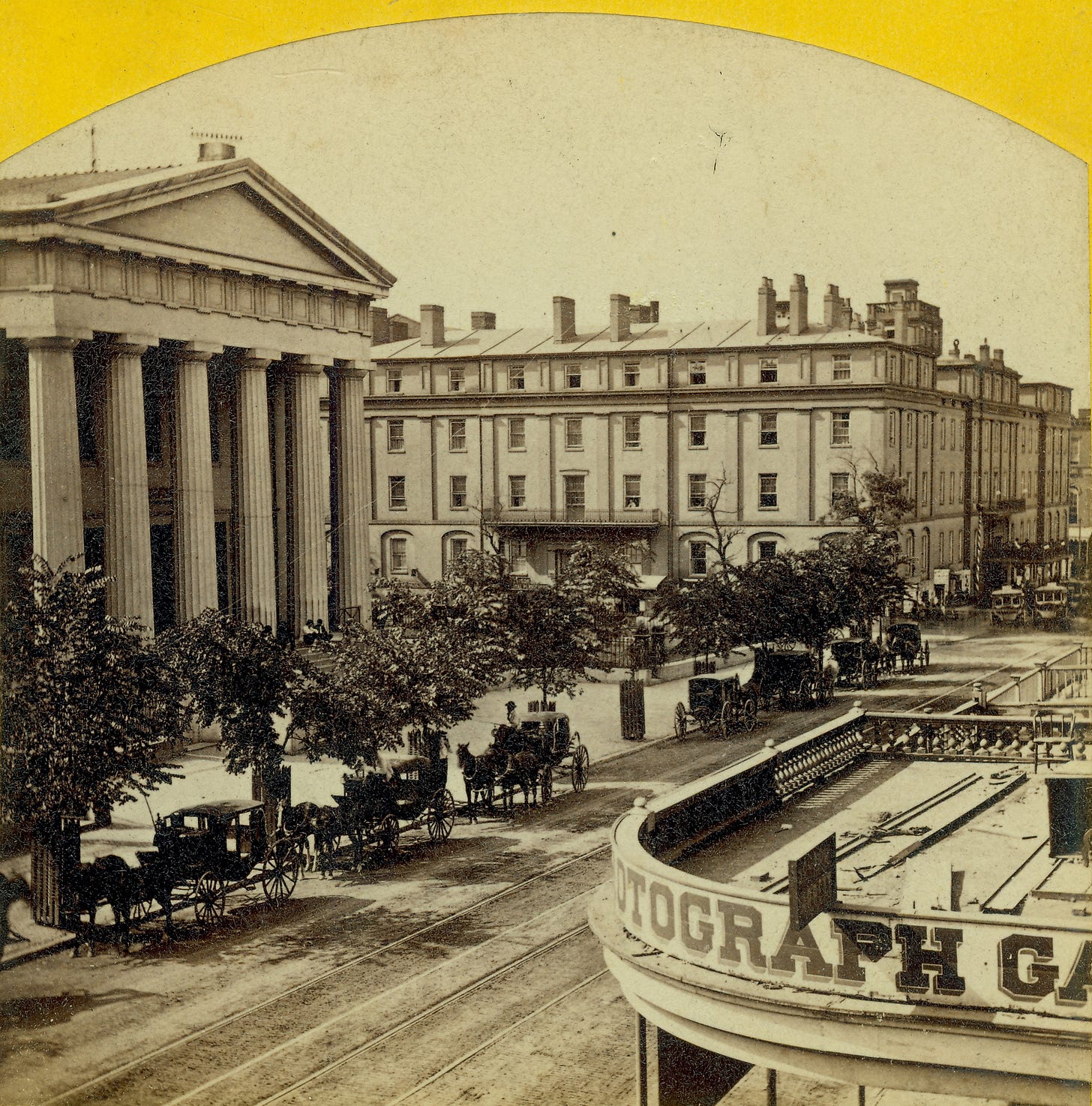

Over four days, many of the same witnesses were called by the defense, albeit the most influential ones: Atty. Vollaire, the parents, and the medical experts. The jury was charged with deliberation on the evening of December 22. On December 24, the foreman reported that the jury once again “agreed to disagree.” I bet Judge Lindley had to employ some anger management techniques to keep a grip at this point. It’s Christmas Eve and he’s getting déjà vu instead of a nice dinner. He promptly told them to march right back to the Planters House (hotel), get back at it, and get the job done.

The Planters House was a luxury hotel and much ado was made afterward about the bill, which amounted to $315.00. Jurors were accused of “being of that numerous class who, having no employment, are glad of an opportunity to pass the time in a warm room listening to a matter in which they feel but slight interest, and caring little how long the monotony may continue.” The opinions went so far as to accuse childless jurors of not caring about the Christmas holiday since they had no little ones to make merry for. The bill eventually was approved and paid since it had indeed been incurred, but it took almost longer than the first trial.

Much to Judge Lindley’s disgruntlement, the jury remained in the Planters House through Christmas Day. The modern movie Groundhog Day was 117 years in the future, but had it not been, the judge would have thought he was in it. On December 27, Foreman Evans bravely reported they were hopelessly deadlocked, once again, at 10 for acquittal and 2 for conviction. This was the same result as the first trial although with a different jury. Mr. Evans may have required a stiff drink from the inventory of the Planters to face the judge with this news.

Public outcry ranged from lamenting the inability of the legal system to punish those who commit “the last and greatest of crimes” to objecting to the expense of paying and sequestering jurors as well as the attorney and court costs.

In early 1877, Robert’s defense lawyers filed a motion for bail since the prosecution had not indicated they would retry him. On March 17, 1877, Robert was released on $5,000 bail. The sureties for the bail were George W. Hall and John C. Ralston. There were two George W. Halls in St. Louis at the time, one was a lawyer and one a physician, so it was one of the two. John C. Ralston was a partner in Ralston & Freiens, a home construction company. Robert had been sick for several weeks and was pale and drawn. His only reaction was when his father said, “Come home.” He brightened considerably and the family left together.

The state did not re-indictment Robert and he was never retried for the Woodson murder. Meanwhile, Benjamin Sloan had his own trial to get through.

On August 11, 1876, the Court of Criminal Correction placed a $1,000 bond on Benjamin Sloan and he was ordered to appear before a Grand Jury by which he was indicted. He’d lingered in jail for seven months when his trial started on January 18, 1877. Should Benjamin be convicted, the penalty could be imprisonment in the penitentiary up to ten years.

Benjamin had consistently denied knowing about the jailbreak items concealed in the food. There must have been plenty of talk on the street since the newpaper stated that if Sloan did indeed appear for trial, Priscilla Boatright was expected to appear as a witness to testify for him. The paper commented “there is no jury in the world that would convict a mother of endeavoring to save a son who was in imminent danger of suffering the death penalty.” And they were right.

Witness Mathias Shulter, the jailer, described the items as a bone-handled knife and a high quality steel razor that had been toothed to serve as a saw.

Deputy Jeremiah Coakley related his encounter with Benjamin that day and how he and Turnkey Valentine Eberle ran out to find him once the items were discovered. Eberle testified that he had run in the direction of the Boatright home and when he saw a cart traveling the same direction, he hopped on board and found Sloan on it. He said the interior of the jail was lined with boiler iron up to above the head of a man.

William Blackburn, a blacksmith, said Sloan sometimes worked for him. Deputy Shulter brought both the knife and the file to Blackburn after they were discovered and asked if he’d seen them before. Blackburn said he had seen an implement similar to the saw on a day Sloan had been “striking for him.” (A striker swings the sledgehammer while the blacksmith positions the metal.) Benjamin had been grinding it on an emery wheel. When asked, the boy said he used it for cutting picture frames.

Deputy Jailer B.F. Daly testified he could tell the type of metal the items were made of if he tested them, but couldn’t say just by sight. He had tested the saw on the bars of a cell and it “cut in” but wouldn’t have been able to cut all the way through. He said if a man could position himself above the level of the iron cladding in the cell, he definitely could have used the items to dig out the mortar, remove bricks, and escape.

The jury was sent to the city jail to examine the construction, and this marked the end of the prosecution’s case.

Priscilla Boatright was the first called by the defense. Knowing Benjamin worked in a blacksmith’s shop., she had requested he remove the handle and grind down the tang to make a saw. (Note: Her brother, Benjamin, was a blacksmith but she didn’t ask him or he had refused.) Priscilla boldly confessed that she wanted Robert out of jail and didn’t care what it took to get him out. She prepared the meal and hid the tools without any family members knowing about it. She said Sloan only removed the handle of a table knife and ground it. She refused to state who had notched the teeth into it to make the saw, and would only say Sloan had not done it

Robert’s father, Mr. Robert M. Boatright, testified that Sloan was a good boy and had attended Sunday School the morning of the incident. Several other witnesses testified to Benjamin’s character, including a former and current employer.

Benjamin’s cageyness on his visit to the jail, lying about the usual use of the saw, and hiding on a cart after leaving the jail (if that’s what happened) lends weight to him knowing what was going on. But who knows.

The closing statements were made, the instructions were read, and the jury retired for deliberation. After a very short time, they returned a verdict of Not Guilty.

This ends the account of the beginnings of what would become the Buckfoot Gang. I’ll be posting other content while working on the next phase of this family’s story.

Fascinating story! I kept waiting to read the denouement and realized I’d missed it so went back to your stack and found it today. Such a colorful family!

Ah the intricacies of the legal system at work! Good on Priscilla for being forthright - she was fighting for her son’s life and she didn’t care who knew!

Thanks for sharing all the great intrigue, courtroom drama and details of this family story with us! Great work!