Trouble Compounded

Part 2: The Buckfoot Gang

At 1:00 p.m. on Monday, March 15, 1875, in the Old St. Louis City Courthouse, the case of State vs. Charles Woodson regarding the death of Oscar Boatright began. Court cases were not unfamiliar to the Boatrights, although until now their experience had largely been on the defendant side of the courtroom.

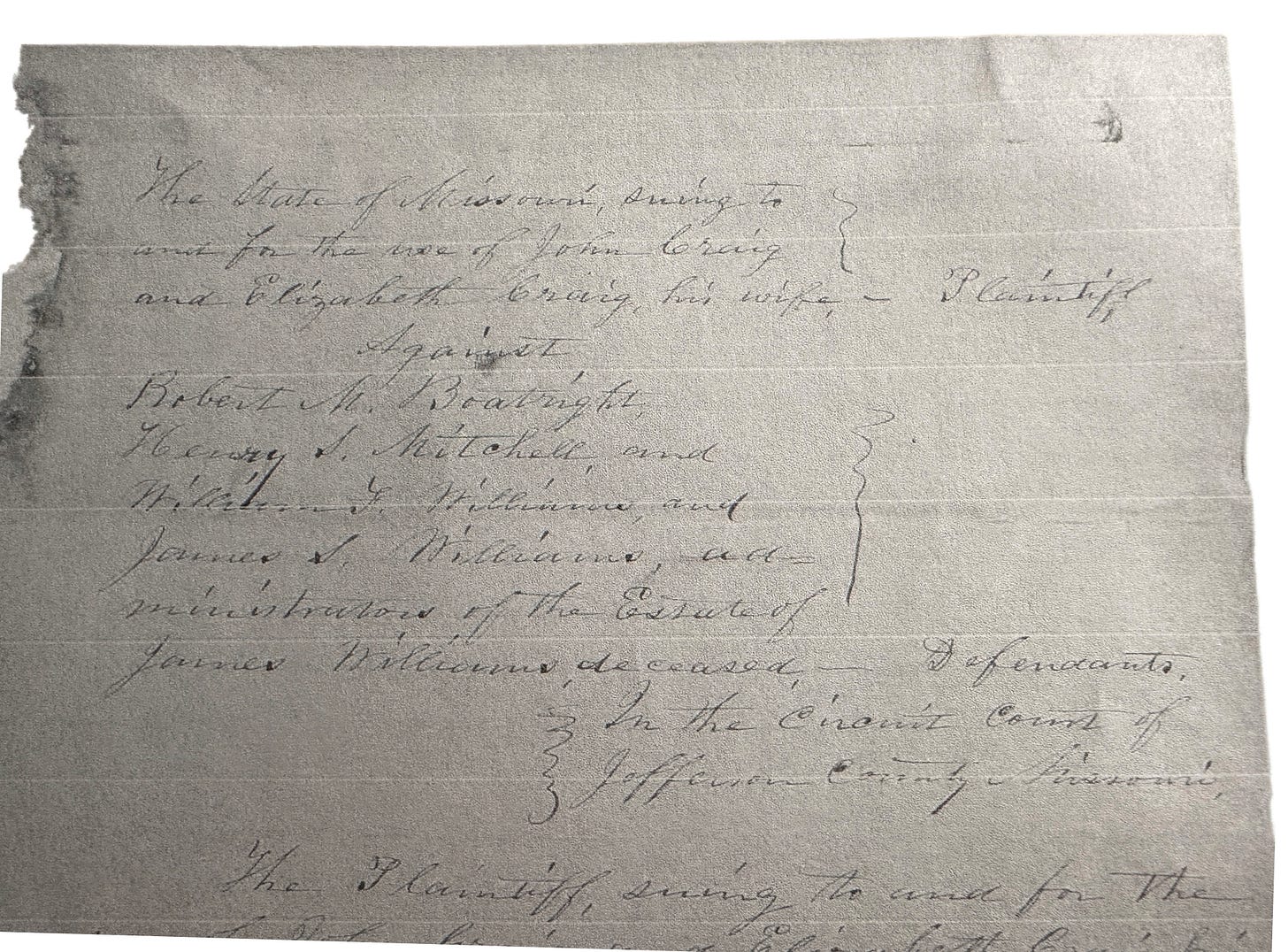

For example, in May of 1861, Robert M (Oscar’s father) was summoned to Jefferson County Circuit Court as one of four defendants in a suit brought by Elizabeth and John Craig regarding a Guardian Bond. Of the other three defendants, at the time of the hearing, one was deceased and the other two were acting as joint Administrators of his estate. I was able to find a copy of the original, hand-written documents which gave a clear explanation of the circumstances.

Elizabeth Craig nee Slone was Priscilla’s sister. John Slone, their father, died while Elizabeth was still a minor; the document says she was fifteen at the time. Robert Boatright, Elizabeth’s brother-in-law, was appointed her guardian at the court’s September term of 1855.

He was also appointed Administrator of John’ Slone’s estate. Regarding those responsibilities, Robert signed a Bond in the amount of $200 if he should fail to perform those duties. The three other men were listed as securities.

By the time the 1861 suit was in court, Elizabeth was married to John Craig and is the Elizabeth Craig noted as a Plaintiff. The suit claims Robert failed to pay Elizabeth’s share of her father’s estate: an amount of $50 in December of 1855 and $48.36 in March 1856, totaling $98.36.

It also states Robert failed to provide annual reports for receipt of any money intended for Elizabeth as required by law. Because Robert failed to provide Elizabeth with the money she was due, the Craig’s were suing for the full Bond amount of $200. Documentation of the outcome was not included. Whether an award was granted, whether it was the $98.36 or the full $200, and if so, where the money came from, either Robert M. Boatright or one/both of the two surviving securities, I don’t know.

Back to 1875. The first witness called to the stand was the victim’s father, Robert M. Boatright. The prosecuting attorney asked him to describe Oscar’s condition after the assault. It appears the defense attorney objected because Robert was not a physician and asked that the jury retire so they would not be prejudiced by what was surely going to be emotional testimony. The objection was sustained and the jury was removed while Robert testified.

After his testimony, the court decided that the physicians who attended Oscar were needed to verify Robert’s statements regarding his injuries, presumably with the jury present, although it didn’t say.

In a far more casual process than is used now, Robert M. called out to his younger son, Robert P., who was in the courtroom, and asked him to run to the doctor’s office and fetch one of the physicians. Robert promptly left to do so.

The courtroom waited. I can imagine the soft sounds of paper shuffling, spectators murmuring, a cough here and there. The article described the defendant Charles Woodson by saying his head barely reached the top of the chair in which he sat. No hint of his demeanor was given, whether fearful or defiant, looking around the room or staring straight ahead.

Robert P. returned only a few short minutes later. With quick, bold strides, he walked smack down the middle of the aisle and into the well of the court. As unusual as this was, even for 1875, the court staff must have thought he had a message from the doctor and forgave the transgression because of his age, 16 years. They did nothing to stop him.

In one of those “it happened before we knew it” moments, Robert stopped beside the chair in which the defendant sat, drew out a long knife, and plunged it into Charles Woodson’s abdomen. They were estimated to be ten feet from the judge’s bench and right in the midst of lawyers and court officers, much like it would be today in a courtroom. It was reported Robert shouted, “You killed my brother, and I will kill you!”

Attorney Voullaire, the prosecutor, leapt from his seat and grabbed Robert’s once again raised arm, knife poised for another strike. The Court Clerk, Mr. Clabby, hustled over and pried the knife out of Robert’s fingers. Judge William C. Jones rushed from the bench and was joined by Deputy Marshall Horton in restraining Robert who, by now it was said, had already stopped resisting.

Charles Woodson cried out and reached out both arms to his attorney, Charles P. Johnson, before falling over into his lap. He was laid on the floor while the court personnel pushed the crowd back, out of the room, and down the staircase. It caused such a row that Deputy Coroner Praedicow and officers from the police department came running.

Robert P. Boatright was escorted by a Deputy Marshall to Chief Detective O’Conner who packed him off to the slammer and firmly locked the door of Cell #5.

Dr. J.J. O’Brien was in the courthouse on other business when the ruckus happened. He came to the courtroom and began to examine Charles. A mattress was brought by another doctor, Dr. Robinson of the City Dispensary, lacking any type of stretcher.

Dr. O’Brien noted Charles’s injury as a slashing wound, approaching seven inches long, which exposed the lower abdominal cavity, displacing a section of the large intestines. Repositioning was determined to be impossible without further enlarging the wound due to the rapid onset of inflammation and swelling. It didn’t say if any attempt at this was done, or was to be done.

The knife was examined and reported to be about a foot long (butcher knife). It was noted to have been recently ground on both sides and was sharp as a razor. The point was slightly bent. It was thought to have struck a button on the boy’s vest. Notches had been cut along the sides and on one face of the blade, the initials J.B. were inscribed.

When questioned, Robert M. said he had never seen the knife before and had never heard his son threaten to kill Charles. Reportedly, on the way to his cell, Robert P. said he had promised Oscar on his deathbed that he’d kill the one who had killed him. Whether or not this was true or artistic journalism, who knows. But it was, indeed, what he had done.

Robert P. was in the cell with four other boys, and the cell was monitored. Robert reportedly vascillated between bravado and silent scowling. He would lie down on the narrow bench and then be right back up pacing.

Reporters wrote that the elder Boatright had requested two years prior that the court send his son to the House of Refuge because he had become uncontrollable. (It was located on the site of current day Marquette Park.) This was done so there must have been enough evidence for a judge to make that decision. The normal protocol was to hold inmates until they were out of their minority. Unfortunately, during visits, Robert the younger finally managed to convince his father that he’d learned his lesson, he would reform, and he was released. Reform was certainly not something he would do, not then and not ever.

Charles, aka Charley, Woodson was the son of Edward Woodson who had formerly been a slave. Following Emancipation, he became a Baptist preacher. As noted in Part 1, at the time of the first incident involving Charley in June of 1874, Edward worked as a janitor. The article revealed that prior to moving to St. Louis, he had held this same position in the Missouri Supreme Court building.

When Dr. O’Brien was finished with his examination, young Charley was delivered to his home on 16th Street. I can’t even imagine how frightening and horrible this was for Charley and his family. They knew the inevitable outcome. It was just a matter of waiting, and waiting without medical care it seems.

I haven’t been able to find an exact date when Charley died, but it could not have been long. Soon after, Judge Jones scheduled a formal inquest for Friday and that is where we’ll start in Part 3.

$200 was a lot of money in those days! Your family history is amazing! ✨

Well. I wasn't expecting that! Looking forward to Part 3.