If you would like to start from the beginning, the series starts here: In the Beginning: Part 1 The Buckfoot Gang

On the morning of March 11, Attorney James Normile gave the prosecution’s closing statement. He spoke for over three hours. Right off the bat, he aligned himself and the jury as being present as “guardians of the public…for ascertainment of the truth.”

Besides summarizing what had been learned during testimony, Normile delved into the historical figures the defense previously named as examples of men who were considered insane. His explanations regarding their behavior were meant to draw a comparison between eccentricity and true insanity.

He said Martin Luther had a strict and studious mind. Because his work was so vitally important and meaningful, he believed the devil pursued him, but was “perfectly sane” in all other ways.. (Luther was said to have once hurled an inkwell at the devil as he tormented him at his work.) Napoleon I, Normile said, was a sufferer of epilepsy but his mind remained absolutely intact. (It’s theorized that Napoleon had psychogenic seizures caused by intense stress and epileptic-type seizures possibly due to a urethral stricture caused by gonorrhea which produced chronic uremia: decreased ability to urinate which leads to excess fluid and toxin buildup in the bloodstream.)

In response to the defense’s claim that proof of the defendant’s idiocy could be shown by the fact that he had never played with children of his own age, Normile gave the vague explanation that Lord Byron and Isaac Newton were men with scientific minds who had a similar disposition. That settles that.

A portion of his closing argument significantly and visibly distressed Priscilla Boatright. Normile referred to Priscilla’s testimony saying a person would be “unworthy of the respect of humanity if they would not tell a lie to save their son from ignominy, disgrace, and death,” and he was “therefore, charitable to them for the unreliable testimony they gave while on the witness stand.” Oh boy.

Priscilla was reported to have been unable to “endure the insinuations of the speaker without manifesting her bitter anger. Her lips quivered and moved audibly to those very near her.” The reaction of the people watching was obviously one of sympathy for the still-grieving mother and shock at the slight directed toward her.

The Prosecutor dismissed testimony given by the medical expert witnesses as “metaphysical mirage.” He would show the jury the difference between the “healthy atmosphere of the law” and the “the melancholy madness of poetry” which was the opinion of psychiatric physicians. He would show the jury how the doctors were pretenders and not “true pilgrims in the faith.”

Discrediting witnesses when possible is part of a prosecutor’s job, but rather than disparage their assessments as flawed, he is basically throwing the entire psychiatric medical profession under the bus as junk science, asking the jury to give it no more weight than polygraph results (which are no longer allowed in court) or bite mark analyses are today.

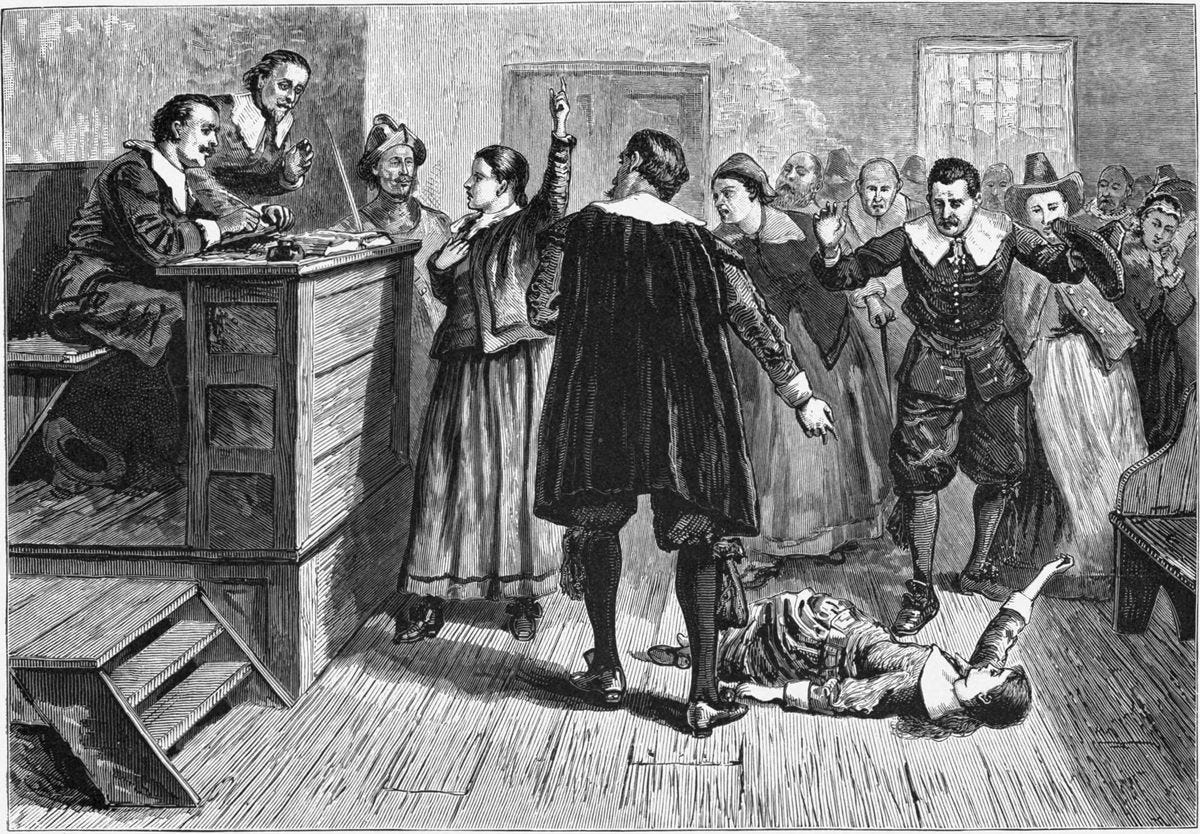

Normile went so far as to compare medical testimony to the pretend science that was so false it had led to the executions for witchcraft in 1692 Salem. He didn’t stop there. He said it was the ancient Romans who founded civilization and the law while the physicians were “humble slaves.” You can’t make this up. Well, maybe a Victorian journalist could…so who knows? The era was rife with drama.

A lot of newspaper acreage was devoted to Normile’s closing argument. He did eventually return to earth by pointing out there appeared to be forethought and concealment in the act and, in an observation recognized by modern criminal profilers, he noted the personal aspect of killing someone with a knife. He also rightfully said the public deserved to be protected from those who would do such a thing, and might do so again. In the end, he made it clear he wasn’t asking for Boatright’s blood, but for him to be banished to the penitentiary or insane asylum for the rest of his life.

Attorney Normile concluded by saying he hoped the jury would not go forth as a laughing stock. (Insert emoji of choice here.)

Just after 2:00 p.m. Judge Lindley gave his instructions to the jury. Those instructions included: Key issues in the case, the jury’s role in the deliberation process, what verdict options are available to them (only murder in the first degree was available), the standard of proof based on evidence, and how to apply the law to meet the requirements for those options in order to make a decision. At 2:20, the jury retired for deliberations.

At 6:00 p.m., Judge Lindley asked the jury if they required any printed instructions, a not-so-subtle nudge to get some insight to how the jury was doing. The jury replied they did not need anything. The judge told them he would remain available to them until 10:00 p.m. should they reach a verdict. Sometime after 10:00 p.m., the jury sent word that they were locked and could get no further that night. They were sequestered at the St. James Hotel for the night.

On the morning of March 13, the Jury Foreman, Joseph R. Wendover, rose to address Judge Lindley. The jury stood where they had the night before, they could not come to an agreement, and he saw no possibility of their doing so. They stood at: Conviction 2, Acquittal 10. A hung jury.

I know, not the result I wanted to hear either. The legalities continued, but I’ll not spend the time covering all the details as what you’ve been so kind to have read through already. In the next installment, I’ll summarize the rest of the legal wrangling over this case.

The jury was dismissed.

Defense attorney Francis Turner requested bail for the defendant and asked the judge what he would “fix it at.” Judge Lindley replied, “I won’t fix it at all.” Firing back, Turner blurted out the spicy remark, “in the Criminal Court, it was customary to set bail for the defendant when the jury disagreed.” Reading the room, Defense Attorney Harris quickly offered that perhaps it would be best to set a discussion about bail for a later hearing. Judge Lindley declined to acquiesce (if you know, you know).

We now enter the tit-for-tat phase. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch from May 17 and 22 referred to a new indictment issued following the hung jury. That indictment was still pending when the defense objected because the indictment named the defendant as R.P.W. Boatright rather than Robert P.W. Boatright. So… it was ruled that yes, a new indictment with the Christian name spelled out was required, and this was issued on May 17 by a Grand Jury.

Defense attorneys Turner and Harris were expected in court on Monday, June 5 to deliver their client’s plea to the new murder indictment. The newspaper says, “…for some reason the parties did not appear.” I’d love to know what communications flew back and forth after that, because they did present themselves on June 7 and entered a plea of not guilty. I can just about hear the muffled groans.

A juicy bit of jailhouse news broke the monotony on June 19, 1876. A jailbreak attempt was made on behalf of Robert Boatright.

Theatre is a good way to describe the court process - everyone is playing a part. Some people know more than others (generally everyone except the defendant) as they have experienced it before. Showboating is another word for it.

Wow! Drama big time. When I was in undergrad, I used to bring a sandwich and sit with the seniors in the gallery of criminal court near my campus, but we rarely got anything even close to this. This post is wild. Love the end note.